By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

With major pro sports — Sonics, Seahawks, Mariners — entrenched in Seattle, and the Star of the Year program (78th is Jan. 25 at Benaroya Hall) having become a popularity contest decided by banquet attendees who had the power of the vote, amateur athletes, except for University of Washington football players, and women had little opportunity to win.

Two women claimed Man of the Year awards in the 1950s (see Wayback Machine: Sports Star Of Year 1950-59), when the program went by that name, two more won in the 1960s (see Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year 1960-69), and another pair won back-to-back to lead off the 1970s (see Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year, 1970-79). But in the 1980s, 22 women received nominations, including synchronized swimmer Tracie Ruiz four times, and none won.

The female nominees included the recipients of a combined 10 Olympic medals, the winners of three international marathons, a world figure skating champion and an NCAA gymnastics champion — but it didn’t make a difference.

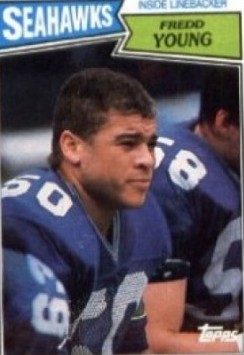

Five Seahawks — RB Curt Warner (1983), coach Chuck Knox (1984), WR Steve Largent (1985), LB Fredd Young (1986) and FB John L. Williams (1988) — won Star of the Year awards in the 1980s. Oddly, neither quarterback Dave Krieg, who played his way into the team’s Ring of Honor during the decade, nor five-time Pro Bowler Kenny Easley, appeared on a Star of the Year ballot.

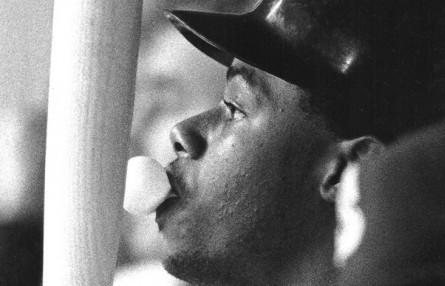

Two UW football nominees — head coach Don James in 1981 and his placekicker, Chuck Nelson, in 1982 — also won. The Sonics had their fourth winner (Jack Sikma, 1980) and the Mariners finally had their first (Ken Griffey Jr., 1989), after a dozen years of blankings.

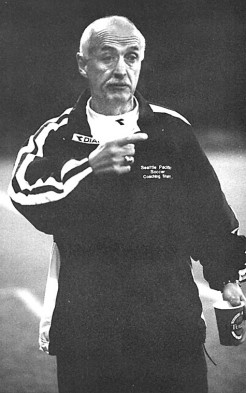

In only one year did a Star of the Year nominee from a lower-profile sport prevail, that in 1986 when Seattle Pacific soccer coach Cliff McCrath, a three-time candidate, won. It took McCrath’s fourth NCAA Division II championship and National Coach of the Year award to push him over the top.

1980 / JACK SIKMA, Basketball

Only five individuals had a realistic shot at winning in 1980, a group that included three frontrunners and two longshots. The favorites, Efren Herrera of the Seahawks, UW football coach Don James, and SuperSonics center Jack Sikma, all had the requisite public profiles, plus achievements to match.

While Herrera, Seattle’s stumpy placekicker, had not produced his best season — he made 20 of 31 field goal attempts — few Seahawks were more popular, especially after an Oct. 29, 1979, Monday Night Football game in Atlanta (Seattle’s first on that stage) in which Herrera caught a 20-yard pass from Jim Zorn for a first down on a fourth-down, fake field goal attempt. The sight of Herrera waddling through the Falcons secondary and snagging a pass that set up a Seattle score endeared him to all Seahawks fans.

It hadn’t hurt Herrera’s persona, either, when head coach Jack Patera, without trying to, turned his kicker into a sympathetic figure. Asked to comment after a 1980 game about a Herrera field goal miss, Patera said, ”He probably ate bad enchiladas.” The public rose in ire — no tweets in those days, but plenty of letters to the editor — and chastised Patera for his racial insensitivity.

James made the ballot for the first time after coaching the Huskies to a 9-3 record and a first-place finish in the Pac-10 Conference. Although Washington lost the Rose Bowl, 23-6 to Michigan, it had become clear James revitalized the UW football program he inherited from Jim Owens. James followed up a 1978 Rose Bowl victory with a 1979 Sun Bowl triumph over Texas. Bottom line: three bowl appearances in his first seven seasons, or as many as Owens managed in 18 years.

The third frontrunner, Sikma, appeared on the ballot for the first time after averaging 14.3 points and 11.1 rebounds in 82 games, and making his second NBA All-Star team for a club that had gone 56-26 and finished second to the Los Angeles Lakers in the Pacific Division.

The two longshots: Mariners representative Bruce Bochte, who had hit an even .300, and Roger Davies, the Sounders striker who had out-performed every athlete on the 1980 ballot. His 25 goals for a 25-7 team led the North American Soccer League, and made him a unanimous choice as the league’s Most Valuable Player, beating out Giorgio Chanaglia of the Cosmos and George Best of the L.A. Aztecs.

While banquet voters went for Sikma, the highest-profile athlete on the ballot by a substantial margin, the best story belonged to the lowest-profile nominee, 30-year-old Craig Fronk, the first skydiver to appear in the Man/Star of the Year finals.

An Issaquah native, Fronk had led a five-member U.S. team on a jump out of an airplane 115 miles short of the North Pole, setting a record for the northernmost skydiving expedition (a jump directly over the North Pole was ruled out because of poor weather).

Fronk, also captain of the U.S. World Skydiving team, told an interviewer that the most difficult part of his feat was landing the plane to set up a base camp, owing to a shifting ice pack 80 miles from the North Pole that kept moving the landing field.

Fronk’s team jumped from 7,500 feet into air estimated to be 60 to 80 degrees below zero. After the team landed successfully, it opened two cases of champagne donated by Ambercrombie and Fitch.

A veteran of 3,000 jumps, Fronk had also led the U.S. parachute team that won the 1979 World Championships in Chateaureaux, France, and he owned the most compelling statistic among the eight Star of the Year nominees: Fronk had 24 cumulative hours of free fall to his credit, or one entire day of plummeting to earth.

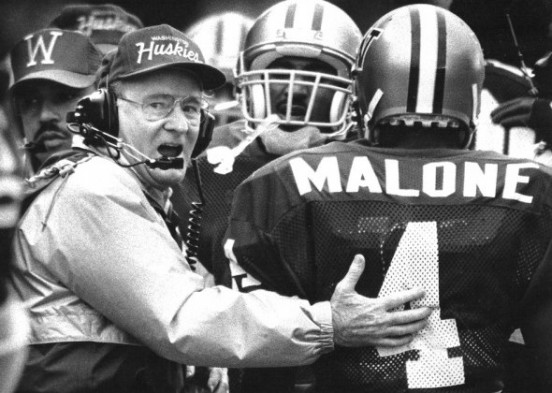

1981 / DON JAMES, Football

Given the history of the program, it did not require a soothsayer to figure out which of the 11 1981 nominees, including three women, would win. Since the Washington Huskies had followed a 10-2 regular season and Pac-10 regular-season title in 1981 with a 28-0 shellacking of Iowa in the Rose Bowl, UW head coach Don James, on the ballot for the second time, was such an obvious pick that no vote was necessary (every other time the Huskies had won a Rose Bowl, the UW nominee won).

Had James not been on the ballot, Fred Brown of the Sonics, a 15.5 points per game scorer in 1980-81, would have been a laudable winner. Same went for the Sounders artful midfielder Alan Hudson, WSU quarterback Clete Casper (second active Cougar athlete nominated following Jack Thompson in 1976 and 1978), who had directed the Jim Walden-coached team to a surprising 8-3-1 record.

The three female nominees, rower Kristi Norelius, synchronized swimmer Tracie Ruiz and figure skater Rosalyn Sumners, all sported award-winning credentials, but none had yet reached her acme of accomplishment.

Norelius, who helped the UW women win the 1981 National Collegiate Rowing Championships, was still three years away from winning a gold medal in eight at the 1984 Summer Olympic Games.

Ruiz, who in 1981 captured the first of what would become six U.S. national synchronized swimming titles, had three Olympic medals in her future — two golds (solo and duet) in 1984, and a silver (solo) in Seoul, Korea (1988) — and 41 total gold medals in all competitions, including Olympic, World and Pan American.

Sumners, fourth at the U.S. Figure Skating Championships, had a World Championship (1983) and an Olympic silver medal (1984) waiting for her.

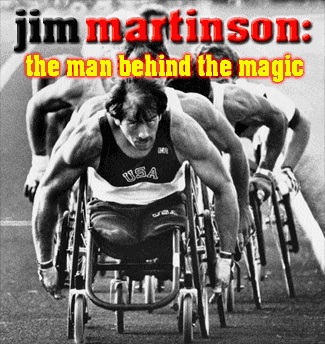

The 1981 ballot also included, for the first time, a wheelchair athlete, Puyallup native Jim Martinson, by far the most inspiring nominee.

As a youngster, Martinson had picked berries, dug ditches and worked on a Forest Service trail crew in order to afford lift tickets at Crystal Mountain. After developing into a first-rate downhiller, Martinson received his draft notice. He shipped out to Vietnam at the onset of the 1968 Tet Offensive, and was deployed into a jungle for search and destroy missions. This is how Martinson, in an interview years later, described what happened:

“There was this incredible explosion. I didn’t realize I was hurt, then I looked down and saw that my right index finger was missing.”

At that moment, Martin hadn’t realized he was also missing most of both of his legs. Medics lifted him out to Da Nang and eventually to Japan. A month later, he checked into Madigan Hospital in Tacoma.

Nine months later, Martinson could walk on prosthetic legs, but had trouble handling his injuries. He turned to drink, became soft and overweight, and hated his own existence. Eventually, some of Martinson’s peers challenged him to join them in an annual race in Tacoma, the Sound to Narrows, which had a 7.5-mile wheelchair division.

Martinson trained for two months, finished the course, and his life changed.

He was nominated for the 1981 Star of the Year award for having won that year’s wheelchair race at the Boston Marathon in a near-record time of two hours, 41 minutes.

1982 / CHUCK NELSON, Football

The 1982 Star of the Year ballot included a future member of the Motorsports Hall of Fame, one of the more colorful characters ever to don a Seattle Mariners uniform, and a precocious 12-year-old little big man who had wowed baseball the previous summer with his exploits at the Little League World Series in Williamsport, PA.

Making his first appearance at the Star of the Year banquet, hydroplane driver Chip Hanauer succeeded in establishing himself as the sport’s top driver and a fitting successor to predecessors Bill Muncey and Dean Chenoweth, both of whom had been killed while piloting speedboats. Hanauer won five races in the summer of 1982, including the APBA Gold Cup, and was trying to become the first hydroplane representative to prevail at the Star of the Year awards since Muncey in 1962 (he was also the first hydro nominee since Billy Schumacher in 1975).

The Mariners’ nominee, Bill Caudill, saved a franchise-record 26 games the previous summer. He was also famous — Sports Illustrated profiled him in a long article for his wild clubhouse and hotel room pranks, as well as his entrepreneurial acumen. Before one day game, Caudill set up a souvenir stand in the Kingdome parking lot and sold $500 worth of team merchandise in 40 minutes.

Caudill also enjoyed dressing up as Sherlock Holmes. He had the full regalia — deerstalker hat, calabash pipe and a couple of magnifying glasses, which he used to “inspect the bat rack for missing hits,” as he liked to say. Thus his moniker, ”The Inspector.” (His other nickname, “Cuffs,” stemmed from his insistence on handcuffing people to fixed objects, such as railings, and leaving them there.)

In his Kingdome locker, Caudill kept two stuffed pink panthers, a Beldar the Conehead mask and several dozen boxes of Jell-O, just in case any prank requiring Jell-O popped into his mind.

Somehow, Star of the Year voters did not have the collective sense of humor to bestow the award on The Inspector, and they similarly dismissed the 12-year-old, star pitcher and hitter Cody Webster, despite his heroics for the Kirkland National team in the Little League World Series, in which Webster punctuated the championship game with the longest home run ever seen in Williamsport.

The University of Washington’s Chuck Nelson became a predictable winner, but a deserving one. Nine selecting organizations, from The Associated Press to the Walter Camp Foundation, named Nelson first-team All-America. No other Husky had ever been named to more than five All-America teams (only one future Husky would make nine All-America first teams, Lawyer Milloy in 1995).

Nelson also established five individual NCAA kicking records, most notably a career streak of 30 consecutive field goals made, and the highest percentage of both extra points and field goals made in a season and a career.

Originally a walk-on at Washington, Nelson spent five years in the NFL, with the Rams, Bills and Vikings. On Jan. 9, 1988, Nelson set a Minnesota record by kicking five field goals in a playoff game against San Francisco.

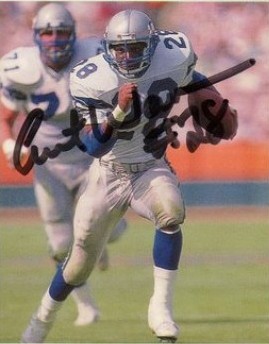

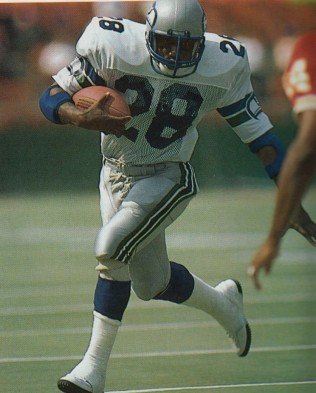

1983 / CURT WARNER, Football

In order to move up and acquire the No. 3 overall pick in the 1983 NFL draft, the Seahawks had to trade three draft picks to the Houston Oilers, their own No. 1 choice, plus two lower picks. The Seahawks still have not made many better deals.

Running back Curt Warner ripped off a 60-yard run on his first professional carry (at Kansas City), went on to amass 1,449 rushing yards and 13 touchdowns, and earn a Pro Bowl berth.

Warner made the job easy for Star of the Year voters, who assessed 10 other nominees, finding much, but ultimately not enough, to keep Warner from winning.

The synchronized swimming tandem of Tracie Ruiz and Candie Costie won gold medals at the Pan American Games; Washington quarterback Steve Pelluer was the Pac-10 Offensive Player of the Year, Rosalyn Sumners of Edmonds captured the ladies title at the 1983 World Figure Skating Championships, and UW long-distance runner Regina Joyce, the Fiesta Bowl Marathon (first marathon she entered).

Also, and for the third time in event history, an animal made the finals, a thoroughbred named Chinook Pass, about whom Hall of Fame jockey Laffit Pincay said repeatedly, ”He is absolutely the fastest horse I have ever ridden.”

Based at Longacres, where he established a world record for five furlongs, until 1983, Chinook Pass moved to Los Angeles, where his owner, Ed Purvis, hoped to cash in on the more lucrative purses available at Santa Anita and Hollywood Park.

As a four-year-old, Chinook Pass won five of seven stakes races in Southern California, became the first Washington-bred to win an Eclipse Award (champion sprinter), then returned to Longacres where, under Pincay’s urging, won the Mile by six lengths despite a cracked bone in his leg.

But 1983 belonged to Warner, who ran for 55 touchdowns over seven years in a Seattle uniform, and might have tallied a lot more if not for a devastating knee injury he suffered at the start of the 1984 season.

Given that Star of the Year voters already set a precedent by including non-Seattle athletes on the ballot (WSU’s Jack Thompson in 1976 and 1978 and Clete Casper in 1981), it marked the single biggest omission in awards program history when the nominating committee left White Pass, WA, alpine skier Phil Mahre off the 1983 ballot. That year, Mahre had become the first American to win three consecutive overall World Cup titles.

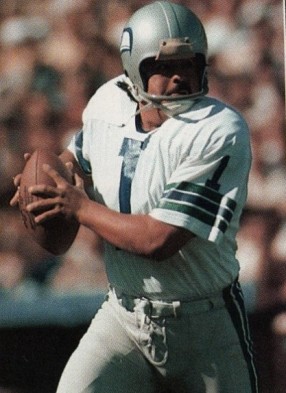

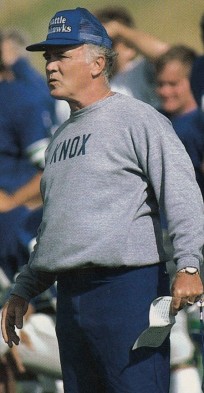

1984 / CHUCK KNOX, Football

Trying to determine a Star of the Year winner in 1984 presented a challenge: How to choose from a nominee slate that included five Olympians who had collectively won seven gold medals, a jockey who had smashed every Longacres record imaginable, an All-America football player, and the American League Rookie of the Year?

Seattle’s Debbie Armstrong had rocked the Olympics Alpine skiing world by winning the women’s downhill in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia, the previous winter, the first and only victory of her long, World Cup career.

Betsy Beard represented a slew of Husky oarswomen who won the eight the previous summer at the Los Angeles Games, where she had been joined atop podiums by fellow Washingtonians Bill Buchan (sailing), Mary Wayte (2 golds, swimming) and Tracie Ruiz (2 golds, synchronized swimming), appearing on the ballot for the third time (also 1981 and 1983).

If any modern-era jockey had a chance of joining Gordon Glisson (1949, see Wayback Machine: Sports Star Of Year: 1935-49) as the only riders to win the Star of the Year award, it would have been Gary Stevens, who rode 232 winners at Longacres, obliterating his own track record by 68 wins.

And Alvin Davis would have been a laudable choice as the first Mariner to win the Star of the Year: 29 home runs after an early-season call-up from AAA that netted him the American League Rookie of the Year award in a close vote over teammate Mark Langston.

That Seahawks coach Chuck Knox prevailed in the vote said more about the popularity of his team than a lack of appreciation for his fellow nominees. Knox and the Seahawks simply had too much mass appeal after romping to the best record in franchise history, 12-4 — without star running back Chris Warner, lost for the year in the season’s opening game after blowing out a knee against Cleveland.

Knox made a key adjustment when Warner went down. Instead of insisting on trying to run in Warner’s absence, Ground Chuck morphed into Air Chuck. Milton College alum Dave Krieg, who joined the club as an undrafted free agent, threw an unlikely 32 touchdown passes as the Seahawks just missed on an opportunity of playing in the AFC Championship game.

En route, the Seahawks put together an eight-game winning streak that wouldn’t be topped until the 2005 Super Bowl-bound Seahawks clipped off 11 in a row.

Unlike his 11 rival Star of the Year nominees, Knox never broke a sweat. Star of the Year voters didn’t care.

1985 / STEVE LARGENT, Football

By 1985, it was obvious that if Steve Largent of the Seahawks could avoid serious injury, and if his production remained constant, he would own every NFL pass receiving record by the time he retired.

Coming off his best season in terms of receiving yardage (1,287), Largent already produced seven 1,000-yard campaigns, scored 79 of what would become 100 career touchdowns, and played in the fifth of what would become seven Pro Bowls. On top of that, he had evolved into a Pacific Northwest icon.

With Largent seated at the head table for the program banquet, no one else on the ballot had much of a chance to claim the Star of the Year award.

Phil Bradley of the Mariners hit .300 with 26 home runs, and smacked a rare ultimate grand slam, a walk-off homer (April 13) with his team trailing by three runs in the bottom of the ninth. But with his ballclub mired in the slowest crawl to .500 in major league history, Bradley had no chance against Largent.

Neither did hydroplane driver Chip Hanauer, on the ballot for the second time (APBA Gold Cup winner), nor decathlete Mike Ramos of the University of Washington, curiously nominated in the only year between 1983-86 that he did not win the Pac-10 or NCAA decathlon title.

By winning, Largent also placed jockey Gary Baze (also nominated in 1973, 1974 and 1982) on a list with bowler Johnny Guenther (1954, 1959, 1965, 1966) and hydroplane driver Billy Schumacher (1956, 1967, 1971, 1975) as the only individuals nominated for Star of the Year four times without winning.

Largent’s pace never slacked. After winning the Star of the Year, he played four more NFL seasons before retiring in possession of the Triple Crown of receiving: most career receptions (819) most career yards (13,089), most career receiving touchdowns (100).

Jerry Rice ultimately broke all of Largent’s statistical marks, but by that time Largent had entered the Pro Football Hall of Fame as a first-ballot inductee (1995).

1986 / CLIFF MCCRATH, Soccer

At the 1986 Star of the Year awards, banquet voters sifted through several impressive athletic dossiers, including those of Seahawks Pro Bowl defensive end Jacob Green (12.0 sacks), Mariners slugger Jim Presley (27 home runs) and the University of Washington basketball team’s leading scorer, Christian Welp (19.4 ppg).

Voters also considered Xavier McDaniel, a Sonics rookie who had averaged 17.1 points per game, UW All-America football player Reggie Rogers (81 tackles for loss), jockey Vicky Aragon (super Longacres apprentice), and Steve Zungul, the Tacoma Stars leading goal scorer.

Instead of opting for an athlete, voters went for four-time nominee Cliff McCrath, the hugely successful soccer coach at Seattle Pacific University.

McCrath first appeared on the Star of the Year ballot in 1975 (when it was still known as Man of the Year), when Marv Harshman won (see Wayback Machine: Sports Star Of Year 1970-79). He appeared again in 1978, when Lenny Wilkens walked off with banquet honors, and in 1983, when voters couldn’t ignore Seahawks rookie running Curt Warner, a 1,449-yard rusher and Pro Bowler.

But in 1986, McCrath presented a case too compelling to ignore. He coached the Falcons to the fourth of what would become five NCAA soccer championships, and was named National Soccer Coach of the Year.

Before Seattle Pacific parted ways with McCrath in 2007 after a career that spanned 38 years, he was named Conference Coach of the Year a record 19 times, took the Falcons to 30 NCAA tournaments, to national championship games 10 times, winning five NCAA titles, and had the second-highest win total (597) in collegiate soccer history.

Eventually, McCrath would enter seven halls of fame, including the U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame.

An odd note about the 1986 candidates: Except for McCrath, all were first timers, and none would appear on a Star of the Year ballot again.

1987/ FREDD YOUNG, Football

Yumi Mordre, a double gold medalist at the 1983 Pan American Games, joined nine other nominees for the Sports Star of the Year award after becoming the first University of Washington athlete to win multiple disciplines at an NCAA Gymnastics Championships, taking the 1987 vault and balance beam and finishing second in all-around.

Another Husky, Duncan Atwood, became a finalist by winning the U.S. national javelin title, hurling the spear a UW record 280-8.

But neither Mordre nor Atwood, nor Bente Moe, the Norwegian distance runner from Seattle Pacific who had won the Houston Marathon, stood much of a chance with voters, who overwhelmingly favored high-profile professional athletes, such as left-handed pitcher Mark Langston of the Mariners.

Langston produced his best year since 1984, going 19-13 with a 3.84 ERA for a Mariners team that was 78-84. But even that ledger was ultimately insufficient to beat linebacker Fredd Young of the Seahawks.

Langston thus became the 11th consecutive Mariners player not to win the Star of the Year award. He might have been able to sway voters from Young had the Seahawks missed the playoffs, but they didn’t, ending a four-year, postseason blackout.

Young emerged as one of better linebackers in the AFC, a Pro Bowler as a reserve in 1985, then as a starter in 1986 and 1987, when he led the Seahawks with 101 tackles and was named first-team All-NFL by the Associated Press, just the fifth Seattle player so recognized by the wire service.

Young provided the Seahawks with considerably more than outstanding play. When the club could not satisfy Young’s contract demands prior to the 1988 season, it swapped him to Indianapolis for the Colts’ No. 1 picks in 1989 and 1990. Seattle used the 1990 No. 1 on Andy Heck, who started 70 games at three offensive line positions over a five-year span. The Seahawks used the second No. 1 pick from the Colts, plus their own No. 1, to move up in the 1990 draft to select DT Cortez Kennedy, who became an eight-time Pro Bowl player and Hall of Famer.

It didn’t end so well for the 1987 Sports Star of the Year. Young, who had 15 sacks in his two seasons as a starting linebacker in Seattle, had just two in his three seasons with the Colts, and then was done.

1988 / JOHN L. WILLIAMS, Football

By the time synchronized swimmer Tracie Ruiz-Conforto arrived at the 1988 Sports Star of the Year awards, fresh off a silver medal in the Seoul Olympics, she had 41 gold medals in various national and international competitions, including two in the Olympic Games and three in the Pan American Games.

All that got her when it came to Sports Star of the Year awards was a tie with bowler Johnny Guenther (1954, 1959, 1965, 1966), hydroplane driver Billy Schumacher (1956, 1967, 1971, 1975) and jockey Gary Baze (1973, 1974, 1982, 1985) for most nominations without winning (4).

Ruiz-Conforto, who lost in 1981 to UW football coach Don James, in 1982 to UW placekicker Chuck Nelson, and in 1984 to Seahawks coach Chuck Knox, lost again in 1988 when Seahawks fullback John L. Williams triumphed over a field that included Dale Ellis of the SuperSonics (25.8 ppg), IBF lightweight boxing champion Greg “Mutt” Haugen, second baseman Harold Reynolds of the Mariners (12th consecutive Mariner not to win), and a number of remarkable collegians, including a pair from Washington State, unprecedented in Star of the Year annals.

Offensive lineman Mike Utley earned his nomination by making first-team All-America and winning the Most Valuable Player award in Washington State’s 24-22 victory over the University of Houston in the Aloha Bowl.

WSU baseball star John Olerud received his after producing one of the greatest individual seasons in college baseball history. Olerud hit .464 with 23 home runs, 81 RBIs and an .876 slugging percentage. As a pitcher, he had an undefeated 15-0 season with 113 strikeouts and a 2.49 ERA. Baseball America named him its 1988 College Player of the Year (Olerud skipped the minor leagues entirely and went straight to the majors).

But Williams’ candidacy swayed Star of the Year voters, even though Williams had not had a Pro Bowl season, in large part because Pro Bowl voters rarely acknowledged fullbacks, even exceptional ones such as Williams.

Williams finished No. 2 on the club (to Curt Warner) in rushing with 877 yards. More remarkably, he became the first fullback in franchise history to lead the team in receiving, catching 58 passes for 651 yards and three touchdowns.

Williams also led the Seahawks in receiving in 1990 with 73 catches and in 1992 with 74. Most single-season receptions by a Seahawks fullback since: Mack Strong, 29 in both 2003 and 2006.

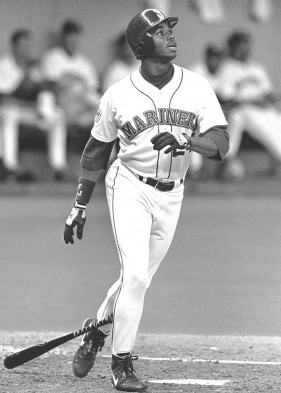

1989 / KEN GRIFFEY JR., Baseball

It took the Mariners (1976-present) a dozen years before they were able to offer up a candidate voters deemed worthy of making the Sports Star of the Year. Ken Griffey Jr., then just 19 years old, could have won it a dozen other times during his career had awards program policy allowed former winners to return to the ballot. But it did not, so Griffey was one and done in his only banquet appearance.

A rookie, Griffey had not been the Mariners leading hitter in 1989, batting .264 to Alvin Davis’ .305. Nor had he led the club in home runs, banging 16 to Jeffrey Leonard’s 24.

But from the moment he made the club coming out of spring training, Griffey was the most exciting player on the team. Plus, he represented the promise of a far better future for a Seattle franchise that had endured pretty much nothing but misery during the 12 years before his arrival.

Despite his youth, Griffey’s elevation to Sports Star of the Year surprised no one, even though he faced off against a litany of qualified candidates, including Bern Brostek, the University of Washington’s All-Pac-10 center who won the Morris Trophy as the top lineman in Pac-10, Longacres riding champion Gary Boulanger, Seahawks Pro Bowler Rufus Porter, Michael Cage of the SuperSonics, and golfer Don Bies, making his third appearance on the ballot (won three Senior PGA events, including The Tradition at Desert Mountain), but first since 1975. Bies set an unofficial Star of the Year record for most years between finals appearances.

Two women appeared on the 1989 ballot, both of whom might have won after women received their own voting category (1994). Shannon Higgins, a Kent native from Mount Rainier High School who had matriculated to the University of North Carolina, was a star player on four consecutive NCAA champions (in 1991, Higgins starred for the U.S. team in the Women’s World Cup, assisting on both of Michelle Akers’ goals in a 2-1 final).

And Lisa Weidenbach, the 1985 Boston Marathon winner (last American woman to win that race) who had relocated to Washington state, won her second consecutive Chicago Marathon. Weidenbach went on to win two more major marathons, Japan (1990) and Twin Cities (1993).

But none of the other nominees rivaled Griffey’s charisma and popularity, and none would ever rise as high in their sports as Griffey rose in his, a first-ballot Hall of Famer-to-be after he played his final game for the Mariners May 31, 2010.

———————————————–

ALSO SEE

Man of the Year Winners (1935-76)

Sports Star of the Year Winners (1977-2011)

Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year (1935-49)

Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year (1950-59)

Wayback Machine: Sports Star of the Year (1960-69)

Wayback Machine: Sports Star of the Year (1970-79)

—————————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

—————————————————–

The Seattle Sports Star of the Year awards program is at Benaroya Hall Jan. 25. Created by Royal Brougham and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1936 and currently presented by the Seattle Sports Commission, the Star of the Year recognizes professional and amateur athletic achievement. Tickets for the event can be purchased at benaroyahall.org or by calling 206-215-4747. The top-priced ticket includes admission to the show and the reception where complimentary beverages, including beer and wine, and heavy appetizers will be provided. You can find more information here. For information about how (and for whom) to vote, go to this page.

The Seattle Sports Star of the Year awards program is at Benaroya Hall Jan. 25. Created by Royal Brougham and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1936 and currently presented by the Seattle Sports Commission, the Star of the Year recognizes professional and amateur athletic achievement. Tickets for the event can be purchased at benaroyahall.org or by calling 206-215-4747. The top-priced ticket includes admission to the show and the reception where complimentary beverages, including beer and wine, and heavy appetizers will be provided. You can find more information here. For information about how (and for whom) to vote, go to this page.

3 Comments

Great article! It brought back a lot of memories. Now I feel old :)

I remember Fred Young being a stud. If I remember correctly, he wanted out of Seattle after we drafted Bosworth?

Fred Brown averaged 15.5 PPG during the 1980-81 season, not 21.9. He did average 21.0 during the 1974-75 season. Gus Williams sat out the 80-81 season and Jack Sikma averaged 18.7 ppg.