By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

After 22 1/2 seasons of confinement in the artificial light and sterile atmosphere of the Kingdome, Seattle Mariners fans reveled in the great outdoors for the first time July 15, 1999, when Safeco Field, constructed for an outlay of $517 million, opened its doors and retractable roof to the nearly universal acclaim of a sold-out house.

Many will recall, if only from innumerable replays, that legendary broadcaster Dave Niehaus tossed out the ceremonial first pitch, hurling it over the head of Tom Foley, the ex-Speaker of the House, stationed behind the plate. Fewer are likely to recall that Jamie Moyer delivered the first official pitch, that San Diegos Eric Owens produced the first base hit, and that Dan Wilson scored the first Mariners run.

A landmark day in Northwest sports history ended badly, if not typically. After Moyer allowed one run over eight innings with nine strikeouts and one walk, he turned the game over to closer Jose Mesa, who gallingly turned it over to San Diego.

A perfect representative of Seattles Gasoline Alley bullpens of those days, Senior Smoke walked four of the five hitters he confronted, becoming the first man in Safeco Field history to get booed off the mound, and the Padres won 3-2.

The Mariners announced an attendance of 44,607 even though the park held 47,155. The discrepancy? Paid attendance was 44,607 and the Mariners issued more than 2,000 complimentary tickets, the media consuming 540 passes, one of which went to Tim Egan of The New York Times, the first reporter to snag a foul ball in the facility.

In the 13 years since Senior Smoke butchered the baptismal, the Mariners have consistently acknowledged Seattles fascinating baseball past, through the Baseball Museum of the Pacific Northwest and Seattle Mariners Hall of Fame, annual Turn Back The Clock games and a nostalgic parade of ceremonial first pitchers.

For Safecos debut, the Mariners introduced nine legends of Seattle baseball, each sporting retro uniforms. The nine included representatives of the Seattle Indians (1922-37), Seattle Steelheads (1946), Seattle Rainiers (1938-64) and Seattle Pilots (1969). No legend had a longer memory than Lou Almada, then 92 years old, and probably none had a better sense of humor.

Following introductions of the old-timers, a sports writer asked Almada for his thoughts on the new park. He said, I think I could hit here. I’d just need someone to run for me.

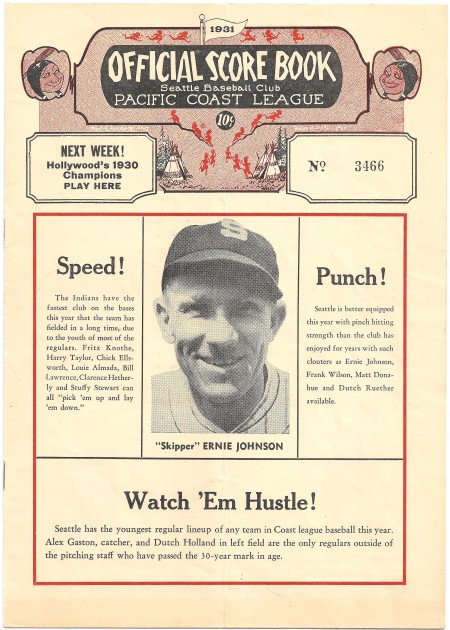

Seventy years earlier, he flew. Almada toiled for the Pacific Coast Leagues Seattle Indians from 1929 through mid-1932, meaning that he played on a string of poor ball clubs at Civic Field under manager Ernie Johnson, an Illinois native whod had a 10-year major league career, and whose notable achievement was helping the 1923 New York Yankees win the World Series.

That place (Civic Field) didnt do him justice, said Edo Vanni, a Safeco Field inaugural attendee who served as clubhouse boy among other duties, he shined Almadas shoes when Almada played for the Indians. “He was an outstanding player.

That wasn’t all he was. Lou Almada, curiously, also became the architect of his own Seattle demise.

Born Sept. 7, 1907, in El Fuerte, Sinaloa, Mexico, Louis Joseph Almada was one of eight children (two boys, six girls) reared by Baldomero and Amelia Almada. Baldomero could trace his ancestry to Portugal, Amelia hers to France.

Baldomero operated a string of ranches on behalf of the Mexican government, but with the Mexican Revolution (1910-20) raging, relocated his family abroad. The Mexican government offered to make Baldomero Ambassador to France, but he declined, and also turned down a position in the Mexican consulate in New York.

Instead, Baldomero chose to work in the Mexican consulate in Los Angeles, mainly because of the citys glorious weather, but also because it was closer to his native Mexico than the New York or France postings.

Within a matter of days of arriving of in Los Angeles, seven-year-old Lou Almada, Baldomero’s oldest son, stood fascinated by a group of men playing softball. When he subsequently saw baseball and a football games, Lou had found his sports, and learned to play both on the L.A. sandlots as he progressed through Jefferson Grammar School and John Adams Junior High School.

At Los Angeles High School, Louie was nearly unbeatable as a pitcher (averaged 14 strikeouts per game) in 1925 and 1926, when he led L.A. High to a pair of city championships, and was such an outstanding quarterback for the Romans that he received scholarship offers from USC and Notre Dame (in the 1960s, in a poll conducted by the Los Angeles Times, Almada was voted the most outstanding quarterback in Romans history).

Voted the Outstanding High School Athlete in the State of California in 1926 (Ted Williams and John Elway later won the same award), Almada rejected both scholarships in order to pursue a baseball career as a pitcher and outfielder.

Almada received widespread attention after his senior when, in the summer of 1926, he struck out Babe Ruth in an exhibition game at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles. Sam Crawford, a scout for the New York Giants and one-time teammate of Ty Cobbs, saw Almada that day and invited him to the New York Giants spring training camp in 1927, signing him to a $5,000 contract.

One year out of high school, Lou reported to the Giants, quickly earning the nickname The Caballero from California. Good as he’d been in high school, Lou wasnt quite ready to play ball with future Hall of Famers Burleigh Grimes, Rogers Hornsby, Freddie Lindstrom, Mel Ott, Ed Roush and Bill Terry.

Lou had a difficult time retiring major league hitters during spring training games and, when he pressed, he was plagued by wildness. After Lindstrom nailed Lou with a line drive in an exhibition game, manager John McGraw dispatched him to the minor leagues for additional seasoning.

Lou wouldn’t have it. Frustrated, homesick and alone, according to author Gilberto Garcia, who wrote extensively about Almada, Lou quit the Giants and returned to California. Had he stayed, Lou probably would have become the first Mexican national to play in the major leagues.

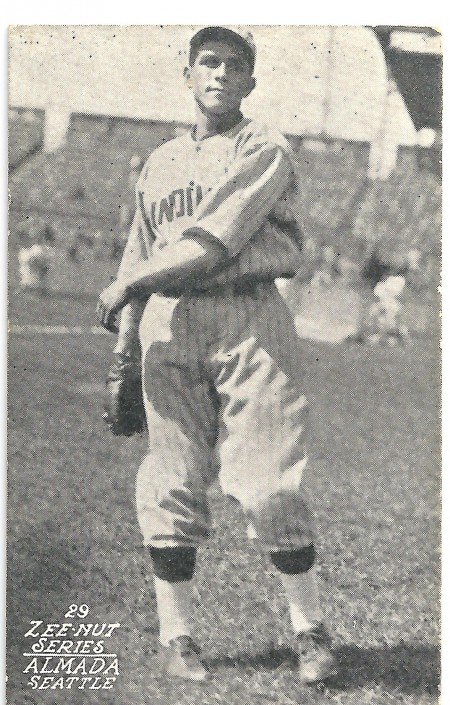

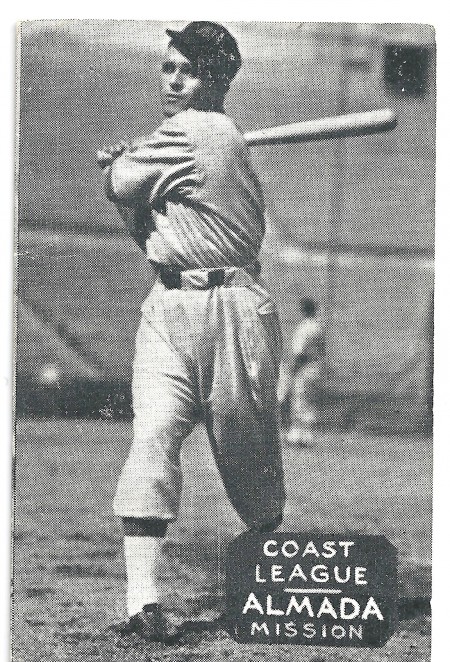

Almada signed with the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League, but wasnt quite PCL ready either, and began his conversion from pitcher to outfielder with the San Clemente Dons, a town team. Shortly after the Seattle Indians launched 1929 spring training in Santa Cruz, club president Bill Klepper and manager Ernie Johnson both saw Almada play. Klepper signed Almada to what was essentially a make-good deal that cost Klepper only the ink on the contract.

The 21-year-old Almada impressed throughout spring training and won the last Indians roster spot, but only after Klepper, in one of his many cost-cutting moves, sold off his highest-paid player, outfielder Wallie Hood, to Memphis of the Southern Association.

As spring training drew to a close, manager Johnson offered this assessment: As an outfielder, Louie is as fast as anyone on the club chasing fly balls. What is as important, he knows where to throw the baseball. The little Mexican is far and away the best ground coverer and also packs an accurate and powerful arm.”

Almada hit .305 in his rookie year and .296 and .289 in two subsequent seasons, which coincided with the onset of the Great Depression, whose impact forced many teams, including Seattle’s, to create special, half-price nights for women in order to increase attendance and revenues.

Thursday became Ladies Day (or night) in the Pacific Coast League and nobody owned Ladies Day like Lou Almada, whom a sports writer, noting his high batting average on Thursdays, famously dubbed him Ladies Day Louie for performances such as these:

- Thursday, Aug. 22, 1929: Belted a home run and a double in Seattles 4-3 win over the Los Angeles Angels.

- Thursday, May 9, 1930: Went 3-for-3 with a home run in a 7-5 win over the Portland Beavers in the first game of a doubleheader, and 3-for-6 in the second game, a 7-2 Seattle win.

- Thursday, June 6, 1930: Broke a scoreless tie in the sixth, when he lined a home run over the right wall to score Dutch Holland in a 5-2 victory over the Oakland Oaks.

- Thursday, Aug. 7, 1930: Belted a home run in an 8-1 victory over the Mission Reds, after which a story in the Post-Intelligencer noted, Kelly dropped Lawrences high fly and the vocal chorus was even louder. Then Freddy Muller tripled to the scoreboard and eardrums popped right and left from the thunder of applause. No, I am wrong. That was only a whisper compared to the noise when Ladies Day Louie Almada lofted a homer over the right-field fence for the fourth and fifth runs of the inning.

- Thursday, Sept. 5, 1930: Had two hits and two RBIs in a 7-6 Seattle victory over the Sacramento Solons.

- Thursday, Sept. 25, 1930: Smacked a walk-off home run off Art Delaney, giving Seattle a 3-2 victory over Sacramento.

- Thursday, April 23, 1931: Went 3-for-5 with a pair of doubles in a 12-7 win over the Missions Reds.

Ladies Day didnt always work out entirely in Louies favor. After the April 23, 1931, game, Alex Schults wrote in The Times, Ladies Day Louie dropped one fly yesterday and didnt try for another that he should have fielded. The wind had him dizzy.

Louie’s play with the Indians made him famous in Mexico. Following the 1930 season, the PCL appointed Almada captain of a Coast League squad assembled to play several exhibition games in Mexico City.

Almada is a hero in our national capital, said A.L. Castillo, a Mexican diplomat. Newspapers publish his photograph often, and its page one news whenever he breaks up a ball game.

In early 1932, with Almada about to enter his fourth season with the Indians, he arrived in spring training with his younger brother, 18-year-old Mel, in tow. Louie had paid Mels traveling expenses to camp because Klepper refused to take a chance on such a young player.

Hes good, Louie told manager Johnson. Mel can help this club right now.

After Johnson worked out Mel a few times, he urged him to stop pitching and concentrate on being an outfielder, as Louie had done. Mel also had a couple of college scholarship offers (same as Louie), but Johnson, according to Colliers magazine (Aug. 24, 1935), told Mel he would be crazy if he wasted his time on a so-called higher education.

Five weeks into spring, Johnson summoned the Almada brothers into his ballpark office in Santa Cruz.

Louie, Johnson said, you were right when you led Mel into camp and said hed be a great ball player. Im keeping him on the payroll and heres your release.

This is how the Post-Intelligencer, under the headline Fate Plays Queer Trick on Brothers, reported the move April 15: Big brother Louie represented his 19-year-old protégé in the conference and signed the papers. Behind the scenes, another story unfolded between the team and the two brothers. The team’s ownership demanded from Louie a cut on his contract, which he flatly refused. This, according to Louie, was the real reason behind his release from the Seattle Indians.

Louie has been an Indian for three years and his outfield work has always been good, but his hitting never has been consistent enough for a Coast Leaguer, wrote Schults, adding a negative note. But Mel looks like a great hitter, judging from his training camp socks and his work as a pinch hitter.

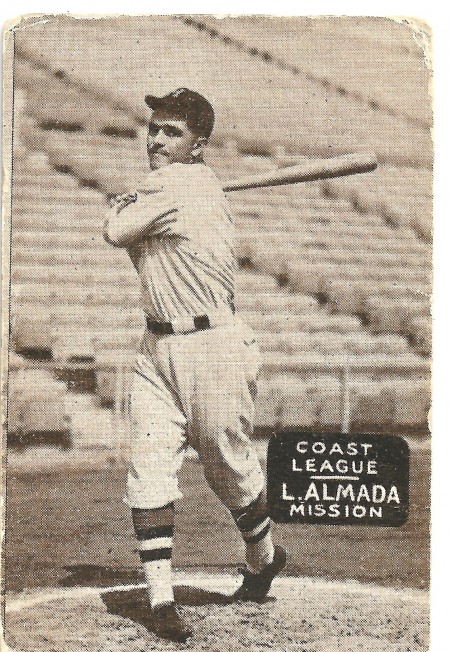

Too bad Johnson couldnt have kept both brothers. Mel hit .311 and .323 in his two years (1932-33) in Seattle, a stint that covered 276 games. Shooed out of the Queen City, Louie immediately caught on with the Mission Reds and produced four 200-hit campaigns, batting a career-high .357 in 1933. In 1934, his average dipped to .332, but he had 265 hits in 186 contests.

The first time the Indians hosted the Reds after Lou’s release, Seattles newspapers splurged ink over the reunion of the brothers.

“It’s quite a show the Almada brothers are putting on this week, opined the Post-Intelligencer as Seattles seven-game series with Mission unfolded. Louie hit a homer inside the park Tuesday night. He hoisted a triple to right in the first frame last night to drive in two runs and picked up a double and a single.”

The Post-Intelligencer also reported, It was a tough break for young Mel as he robbed brother Louie of a base hit by a sparkling catch earlier in the game. Louie and Mel have featured in every game played this week.”

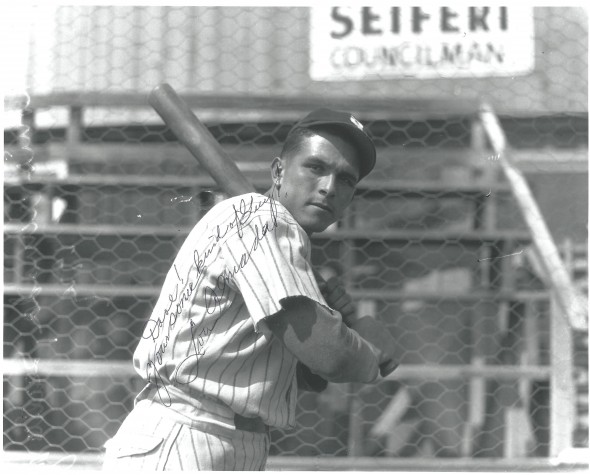

Six years younger than Louie, Baldomero — Melo or (to Americans) Mel Almada arrived Feb. 7, 1913, in Huatabampo, in the state of Sonora, and was an infant when his father brought his family to Los Angeles.

Like Louie, Mel attended Jefferson Grammar School, John Adams Junior High and L.A. High, where he started out as a pitcher. Like Louie, Mel pitched the Romans to Los Angeles city championships (1930 and 1931). Like Louie, Mel played football, rating his first mention in the Los Angeles Times Oct. 26, 1929 for running 53 yards for a touchdown.

Mel also competed in track and field and at one point established a California prep record in the long jump with a leap of 23-4¾. According to the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), Mels prowess in the event prompted a Sporting News cartoonist, in Mels third season with the Red Sox, to dub Mel a Mexican jumping bean.

Mel started slowly after replacing brother Lou in the Indians lineup, sporting a .164 batting average June 5. He raised it to .291 by July 24 and to .308 by the end of the season. Mel played perhaps his best game Aug. 6, going head-to-head against Louie. In five trips to the plate, Mel produced four singles, a triple and scored three runs in Seattles 14-3 win over Mission. Louie had two hits for the Reds.

As early as March, 1933, The Sporting News called Mel the best young outfield prospect in the Coast League. Validating that assessment, Mel batted .331 in May and had one series in which he went 16-for-28 (.571 BA). He had a 16-game hitting streak, a 5-for-5 afternoon April 8 and a string of four-hit games (May 7, June 10, June 20). Such performances intrigued several major league clubs, including the Boston Red Sox and Brooklyn Dodgers, both of which approached Klepper with offers to purchase his young phenom.

News accounts differ on what Klepper received for Mel. One story said Klepper sold Mel to the Red Sox for $10,000 and 1932 PCL home run champion Freddy Muller for $7,500. Another said the Red Sox paid a total of $40,000 for Mel and Muller. Whatever the actual price, The Sporting News wrote in December of 1933 that the sale saved the Indians from financial ruin.

Following the early July sales, the Red Sox opted to leave Mel in the PCL for a couple of months of seasoning before summoning him to Fenway Park, which gave some of his supporters in his native Los Angeles to organize a Melo Almada Day at Wrigley Field. They scheduled it for July 23, when the Indians visited the Angels for a doubleheader.

The Los Angeles Times presented Mel with a gold baseball, calling it a gift from the Mexican colony of Angeles. The tribute to the major league-bound Mel included an appearance by Rita Moreno, one of the famous actresses of the day.

He (Mel) is a dandy chap and deserves this, Bob Ray wrote in the L.A. Times.

Responding to Mels Wrigley Field tribute, several Seattle Indians boosters planned a Mel Almada Day” at Civic Field Aug. 30 in order to give the young outfielder, who batted .323 with 204 hits, a proper sendoff. But rain washed out the event and Mel departed absent a final local cheer.

In 1959, the Red Sox became the last major league team to employ a black player, hiring Jerry Pumpsie Green, whose brother Credell lettered as a running back at the University of Washington in 1955 and 1956, notably producing a 258-yard rushing performance against Washington State Nov. 19, 1955.

But in 1933, the Red Sox became the first major league club to employ a Mexican national, when Mel made his debut Sept. 8 as Bostons center fielder and leadoff hitter. Mel played in both ends of a doubleheader against Detroit and went 1-for-4 in each game.

Had it not been for a burst of wildness, or if he hadnt been hit by the Freddie Lindstrom line drive, the distinction of being the first Mexican national in the majors would have gone to Mel’s brother Louie Almada six years earlier, in 1927.

Mel hit his first major league homer Sept. 23, off New Yorks future Hall of Famer, Herb Pennock, and, on Oct. 1, had a 3-for-3 day against Babe Ruth in Yankee Stadium in the last game Ruth pitched. Mels flurry against the Bambino enabled Mel to finish his first, abbreviated season in the majors with a .341 batting average.

Mel stuck with the Red Sox coming out of spring training in 1934 and in May that year The Sporting News gushed, Mel Almada is now justly regarded as the greatest outfielder Boston has known since the days of the renowned Tris Speaker.

The Sporting News rushed to judgment. Mel did not develop into the next Tris Speaker, but he represented the Almada family quite well in what became, curiously, an extremely brief major league career.

Mel played most of four seasons with the Red Sox (spent the majority of 1934 with the AA Kansas City Blues), hitting .271 in 316 games. After his 135-game exile in Kansas City, he returned to Boston in 1935 and finished third in the American League with 20 steals. After hitting a pedestrian .253 in 1936, the Red Sox traded Mel in 1937 to the Washington Senators, for whom he hit .295.

Although Mel started 1938 in a slump, a June 15 trade to the St. Louis Browns revived him and, for the next 102 games, he was one of the top hitters in the American League, with a .342 average. From June 21-Aug. 19, he had at least one hit in 54 of 56 games, about as close to Joe DiMaggios 56-game hitting streak as a player can get.

Mel had an unusual batting style, The Sporting News describing him as the most pronounced water bucket hitter in the majors. You never saw a guy in such a hurry to keep a date with first base.

By the end of 1938, Mel topped the American League with 158 singles. But plagued by an injured arm, he played his last major league game Oct. 31, 1939, while wearing a Brooklyn Dodgers uniform. He was only 26 years old.

Mel never hit more than one home run in a major league game, and finished with a .284 batting average, but he notably took back to the Pacific Coast League a career-high 29-game hitting streak (July 12-Aug. 11, 1938). Mel also established one major league record, which still stands: On July 25, 1937, he scored nine runs for the Senators in a doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns (3-for-5 with four runs in Game 1, 3-for-5 with five runs in Game 2).

Years after after Mel retired, SABR researcher Carlos Bauer asked Louie Almada why his brother had such a short career. Louie told Bauer, Melo couldnt stand being thrown at. Louie also told Bauer that Mel believed pitchers threw at him because he was a Mexican. Louie told Bauer that his response to Mel was, No, Melo, theyre throwing at you because you are a batter.

According to Bauer, Mel could not be convinced. Word eventually got around that Mel could be intimidated by brushbacks, and pitchers began throwing at him like there was no tomorrow.

Mel signed with the Sacramento Solons for the 1940 season (hit .232 in 104 games) and finished his career with the Torreon Cotton Dealers of the Mexican League as the clubs player/manager. Although he saw action in only 26 games (hit .343), Mel was elected to the Salon de la Fama, or Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame, in 1971.

After his baseball career ended, Mel worked in the produce business in Los Angeles. He joined the Army Medical Corps in 1944 and in 1945 played for the Fort Sam Houston team in the San Antonio Service League. Following World War II, Mel managed Novojoa Mayos, a Sonora entry in the Mexican Pacific Baseball League.

For a while in the 1980s, Mel resided in Tucson, but he eventually returned to Sonora, where he lived the remainder of his days. He died Aug. 13, 1988 of a heart ailment, with barely a mention in American newspapers, but having plowed the road for numerous Mexican players who came to the majors, including Bobby Avila, Fernando Valenzuela and Vinny Castilla. Today, the Mexican Pacific League honors Mel with its Rookie of the Year award, the Baldomero Almada trophy.

After Louies career ended, he went into the produce business in central California, which was why Mel did the same thing, first at the Produce Market in Los Angeles, and later in Nogales, AZ. He retired in 1977, and returned to California.

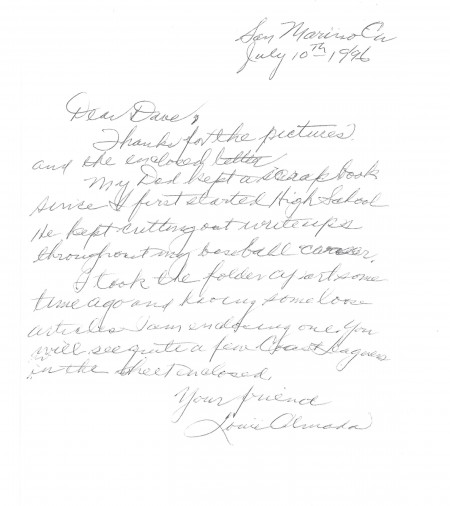

Louie and his wife, Ligia Davila Almada, married 73 years, lived in San Marino, CA., for 50 years before moving to Carmel in 1999, the year Louie visited Safeco Field for its inaugural game.

Known to friends and family as “Papa Lou,” Louie died at his home in Del Mesa, Carmel Sept. 16, 2005, having just gone deep into extra innings by celebrating his 98th birthday the previous week.

Shortly before he died, the one-time Ladies Day Louie had a final wish. He wanted the words “The Noblest Roman of Them All, in recognition of his days at Los Angeles High School, inscribed on his headstone. His family made it so.

————————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

4 Comments

David, I love the historical detail and color you bring to us via your Wayback Machine posts.This is one of your best. Thank You !

On David’s behalf, thanks for reading!

David, I love the historical detail and color you bring to us via your Wayback Machine posts.This is one of your best. Thank You !

On David’s behalf, thanks for reading!