By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

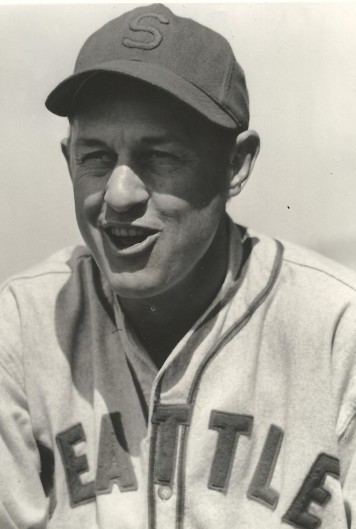

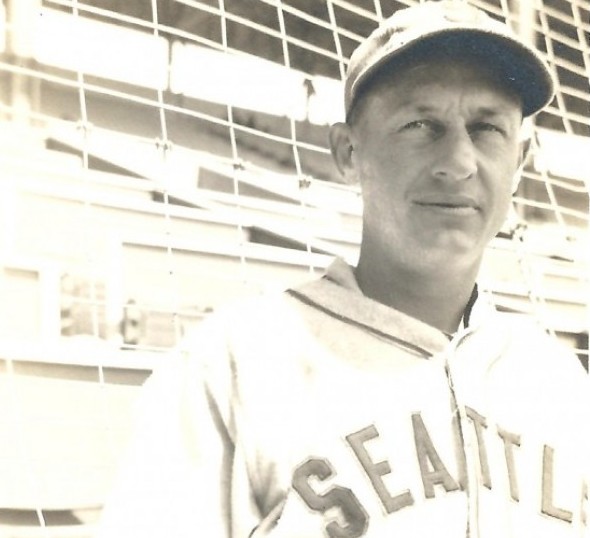

For a long time in the era spanning the baseball seasons 1939 through 1949, Joyner (Jo Jo) White almost ranked as a demigod in Seattle. His celebrity rivaled the kind that Jim Zorn and Steve Largent enjoyed in the 1970s, Jack Sikma and Downtown Freddy Brown had in the 1980s, and Ken Griffey Jr., Edgar Martinez, Gary Payton and Ichiro reveled in after that.

I idolized the man, Edo Vanni, himself a legend during the White years, told the Seattle Times. We roomed together and played together for three years. If Jo Jo told me, Kid, run through that wall for me, all Id have said was, Where do you want the hole?

Where Zorn, Griffey, Payton, Ichiro and others of their station collected paychecks adding into the millions, White gave his heart, soul, love, verve and talent for relatively little. He was born in the wrong time of the 20th century to a become rich athlete.

White, in fact, came into the rock bottom of the Great Depression years of baseball and played in two World Series for the Detroit Tigers in 1934-35.

Such was the concentration of talent in the major leagues, when they consisted of only 16 teams, none west of St. Louis, that many near-great players found themselves relegated to the minor leagues.

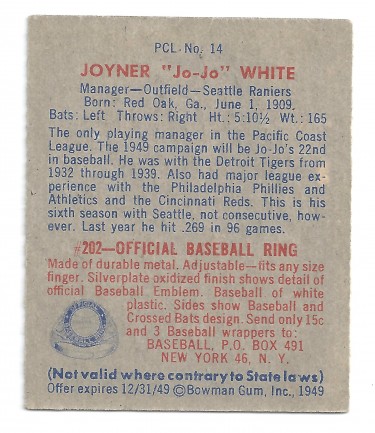

In Joyner Clifford Whites case, it happened like this: Born: June 1, 1909 in rural Red Oak, GA, where he also grew up, White signed his first professional contract at 19 in 1928 with the Carrollton Frogs, a Class D team in the Georgia-Alabama League.

By consistently hitting above .300 during stops at Class C Fort Smith (1929 Western Association), Class B Evansville (1930 Three-Eye League), and Class A Beaumont (1931, Texas League), White had his first whirl in the majors as a 23-year-old outfielder in 1932, making his debut April 15 as a pinch runner for Detroit, which included a future Seattle teammate, outfielder Bill Lawrence, then enjoying his own cup of coffee in the show.

White arrived in the majors already tagged with his famous nickname Jo Jo, having received it during his one-year stint with Evansville. When asked where he was from, the native Georgian drawled Joe-Jah, which morphed into Jo Jo.

Jo Jo hit .260 as a rookie and .252 in 1933, serving as a backup outfielder both seasons. He won a starting job in 1934 and, batting leadoff, put together his best major league season — .313 batting average, 97 runs scored and 28 stolen bases, second most in the American League, as the Tigers won the pennant.

Whites .418 on-base percentage ranked seventh in the American League, and he played in all seven games of the 1934 World Series, walking eight times and scoring six runs against Dizzy Deans Gashouse Gang St. Louis Cardinals.

In 1935, White’s average plunged 73 points to .240, but he still scored 82 runs and ranked among AL leaders with 12 triples and 19 stolen bases.

He played in all five games of the 1935 World Series, scoring three runs with a .417 on base percentage. White also hit a single in the 11th inning of Game 3 to drive in Marv Owen for the victory.

Although only 28, White couldnt hold an outfield job for Detroit after that, largely owing to the crowd of thumpers signed by the Tigers, including future Hall of Famers Al Simmons (.327) and Goose Goslin (.315), both of whom were out-hit by a third outfielder, Gee Walker (.353).

White couldnt quite hit with the three, and the trio also hit home runs, something White almost never did (just eight in 878 major league games). So White returned to backup duty for the next two years.

In 1938, playing in just 55 games, White grew so frustrated over his lack of playing time that, late in the season, during one of the Tigers train trips, he took out his ire on a new felt hat just purchased by manager Del Baker.

White not only ruined Bakers new hat, he ruined whatever chance he had of sticking with the Tigers in 1939. Following the 1938 season, the Tigers included White in a package of players they sent to Seattle in exchange for prized pitcher Fred Hutchinson, who had earned his ticket to the majors with one of the most famous seasons ever put together by a Seattle baseball player (see Wayback Machine: The Rainiers & Pitchers Of Beer).

At first, White refused to report to the Rainiers, who wouldnt meet his contract demands. White, in fact, told The New York Times Feb. 7, 1939 that he had quit baseball and intended to devote all of his time to a job in a Detroit automobile plant. White changed his mind when the Rainiers came through with more money than he ever imagined they would.

The Rainiers paid him $10,000, $2,000 more than he made in his final year with the Tigers. While White never made Seattle fans entirely forget Hutchinson, he became the citys favorite baseball personality for four consecutive summers, not so much with his arm or his bat, although he averaged .296 over four seasons, but with his style of play.

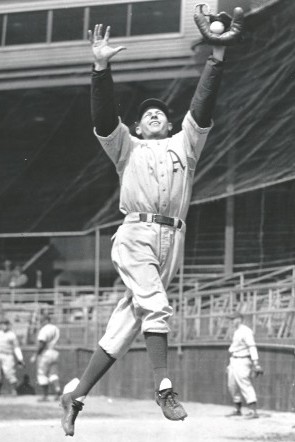

He could run and stir things up, author Dan Raley wrote in Pitchers of Beer. He was the one who came into second base with his spikes high. He was the one who made the deal with the Detroit Tigers pay off and eased the loss of Hutch . . . He roamed Sicks Stadium for four consecutive years and good things seemed to happen each summer.

He led the charge into the glory years of Seattle baseball, wrote Emmett Watson in The Seattle Times. He was a leader on three consecutive pennant-winning teams, 1939, 1940 and 1941, a team that featured such charismatic stars as Dick Gyselman, Alan Strange, Edo Vanni, Earl Torgeson, Gilly Campbell, Ira Scribner, George Archie, Kewpie Dick Barrett and Farmer Hal Turpin, just to name a few.

Those of us who knew him, those of us who thrilled to him in bleachers and grandstand, remember him in our mind’s eye, which plays no tricks on us.

He wore No. 7. He crouched over the plate, bat choked up high, guarding the plate maliciously, daring the pitcher to throw the ball past him; spread stance, digging in the back foot, striking fear and puzzlement into the defense — who knew what he might do?

He could bunt, he could drag, he could fake a bunt and then slash a lethal drive past a bamboozled first baseman drawn in by the fake bunt. He was a choreographer of baseball offense. As a leadoff hitter, he was the arsonist who ignited rallies.

“He walked as though he were dancing on eggshells, on light, quick feet, and when he took suicidally long leads off first, the great crowd at Sicks’ Stadium would chant, “Jo! . . . Jo! . . . Jo! . . . Jo!

And out of the radio booth would come Leo Lassen’s near-scream: ‘There he GOES! . . . Look at him run! In one brilliant year with Alan Strange, a masterful virtuoso of the hit-and-run, he opened up the middle infield with his base-running, and Strange would hammer drives through the vacant holes.

He was the greatest guy I ever knew, Vanni said. He made everybody come to life. He would play hurt and he never complained. He’d even start a fight on his own ball club just to wake everybody up. He helped all the young players. He would take me out early in the mornings and teach me the different slides, and like I say, I idolized him.

White played in 639 games for the Rainiers between 1939-42, at which point the club sold him to Connie Macks Philadelphia Athletics. The Dec. 4, 1942 sale netted the Rainiers utility outfielder Dee Miles and an unspecified amount of cash.

Seattle fans are ready for a pat on the back for Jo Jo, wrote The Times. The slim Georgian gave the Rainiers years of exciting baseball with his spectacular base running and brilliant fielding. Ever since joining the Rainiers, White has burned with a desire to return to the majors, and now he gets his chance.

With the major leagues depleted by the loss of players to World War II, White had no trouble getting playing time with the Athletics. In 1943, he played in more games (139) and had more at bats (500) and hits (124) than any other season in his career.

Midway through the 1943 season, White approached Mack and told the veteran manager of his ambition to run his own ball club when his playing days ended.

Joyner, keep on playing as long as you can, and dont stop until you have to, Mack reportedly told White. The fans love to watch you, and as long as you can please them, you should. As for managing, thats an intangible thing. Do you think you can be a good manager?

Yes, I do, White answered.

Well, so do I, Mack said. If you ever want help getting a managers post, let me know and perhaps I can help you. Im sure youll be a fine handler of players some day.

After playing 85 games for the A’s in 1944, Mack traded White to the Cincinnati Reds when he couldnt get his batting average above .221. Although he did little for the Reds (.235 average), he played the game of his major league life Aug. 26, 1944 at Wrigley Field, going 5-for-6 with a pair of doubles and three RBIs in Cincinnatis 10-7 win over the Cubs.

That winter, White decided to retire as a player, telling his wife Ferne that he thought his legs were shot. But then the Sacramento Solons purchased his contract from Cincinnati and with it came a pay raise that knocked Whites eyes out.

It called for as much money over the 1945 season as hed made in his previous two seasons in the majors combined.

White figured that for that kind of money he had to get more out of his aging legs, and he did, putting together by far his best minor league hitting season.

He batted .355 to lead the PCL, had 244 hits, scored a league-leading 162 runs, and finished second in stolen bases with 40.

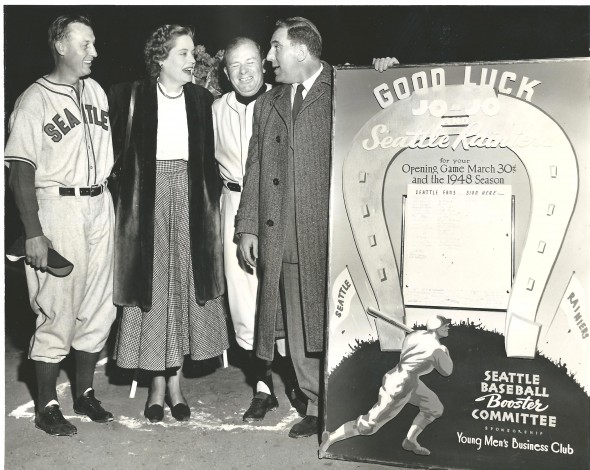

Early in 1946, with White finally fading as a player and the Rainiers needing a replacement for manager Bill Skiff, whose club had skidded into the second division, owner Emil Sick called Sacramento and initiated trade talks, eventually taken over on Seattles behalf by GM Earl Sheely. The Rainiers finally sent Bill Ramsey to the Solons for White.

All thought White would make a superb manager. He didnt, Emmett Watson explaining, He could not play anymore and because he could no longer lead by example, his teams became complacent and unexciting. Though he had the class to teach, lesser men would not listen.

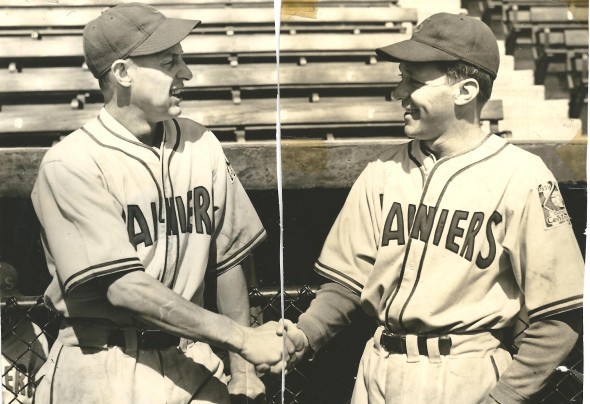

The Rainiers finished seventh under Skiff/White in 1946 and had so-so years in 1947 (91-95) and 1948 (93-95) with White in command. When the Rainiers failed to start strongly in 1949, the club fired their former offensive catalyst (56-54) and replaced him with Lawrence, whom he had played with in Detroit in 1934.

His first time with the club is part of Seattles greatest baseball memory, Watson wrote. The second time, it was never the same.

After his time with the Rainiers ended, White managed San Antonio of the Texas League (1951), scouted for the Cleveland Indians (1953, 1958), and had minor league jobs in Keokuk (Three-Eye League, 1954) and Mobile (Southern Association, 1956).

White returned to the majors in 1959 and coached the Indians through part of 1960 (served as acting manager for one game) until he went to Detroit, switching jobs with Luke Appling Aug. 8 in the famous Jimmie Dykes/Joe Gordon manager swap.

White also coached with the Kansas City Athletics in 1961, the Milwaukee Braves from 1963-65 and the Atlanta Braves in 1966. He also managed the Dallas-Fort Worth Spurs in 1967, scouted for the Kansas City Royals in 1968 and coached the Royals in 1969, the year they entered the American League.

In 1938, a year before White joined the Rainiers, he and wife Ferne became the parents of a son, whom they named Mike. Mike White had a three-year career in the majors, all with the Houston Colt 45s/Astros, and a 10-year minor league run.

Mike spent one of those seasons, 1966, with the Seattle Angels, the last professional baseball team to win a championship in the city (see Wayback Machine: Bob Lemons 1966 Seattle Angels).

When Jo Jo White concluded his baseball wanderings, he returned to the Northwest, settling in Tacoma. Six years after his 1980 induction into the State of Washington Sports Hall of Fame, White passed away (Oct. 9, 1986) at the age of 77.

He loved to gamble and he loved to drink, but he did these things not compulsively, or grimly, but with a good man’s joyous appreciation of what life can be if you know how to live it, Watson wrote. He laughed and sang a lot, in an off-key voice, and out of Georgia he brought a drawl as thick as Southern molasses, with an innate courtliness that drew people to him.

Those of us who knew him will always remember — the bouncy, eggshell walk, the rich drawl, the warmth, the joy, the laughter, and all the rest of it.

——————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com