By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

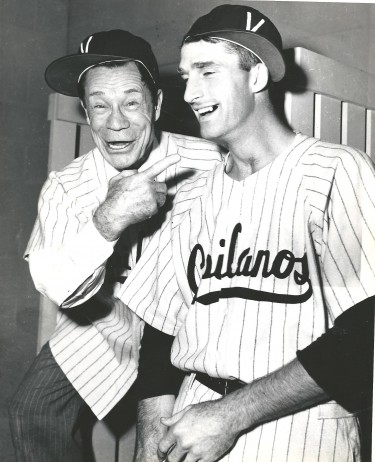

Not many Seattle sports columnists had the audacity to read the riot act to Rogers Hornsby in 1951, the year he managed the Rainiers to a Pacific Coast League pennant. Beyond the fact that Hornsby presided over a successful ball club, he was a Hall of Famer and one of the game’s legendary hitters. Maybe the only thing Hornsby did better than hit was intimidate.

Once, when broadcaster Leo Lassen rubbed Hornsby the wrong way with something Lassen said on the radio, Rajah dressed down and publicly threatened the beloved icon with bodily harm.

Hornsby ragged on many players, Rainiers front office personnel, and sports writers, including Emmett Watson of The Seattle Times, who refused to be cowed by the Rajah’s rants.

“He nearly smothered everyone with his brutish style,” author Dan Raley wrote in his excellent book, Pitchers of Beer.

“Everything was all about Hornsby. No player was exempt from having his confidence shattered. No one was excused from being publicly humiliated by this man.”

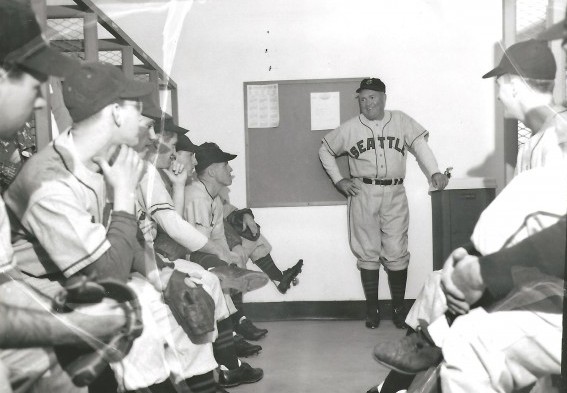

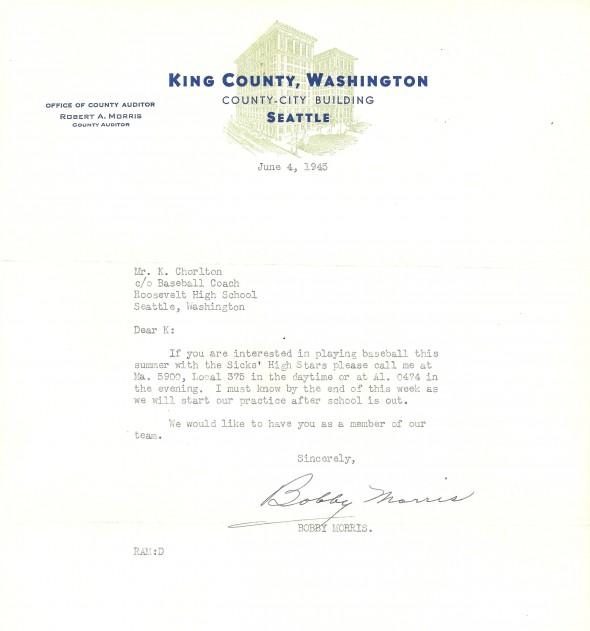

Case in point: In 1951, the Rainiers employed a local phenom-made-good outfielder named K Chorlton – that’s “K” with no period – who starred in multiple sports at Roosevelt High School before launching his professional baseball career with the Vancouver Capilanos of the Western International League in 1949.

During a midseason game, Chorlton somehow allowed a routine fly ball to plunk off his mitt while he was stationed in left field. No huge harm done: There was one out and nobody on base.

“The ball just kind of hit the heel of my mitt,” Chorlton told Georg N. Myers of The Seattle Times. “I guess Mr. Hornsby thought I was just slapping at the ball.”

Chorlton’s misplay so incensed Hornsby that he added to the young player’s embarrassment by holding up an imperious arm and waving him out of the game, replacing Chorlton on the spot with Walt Judnich, who was, according to Raley, as angry at Hornsby as Chorlton.

“That old sonofabitch sent me out to replace you,” Judnich told Chorlton as they passed in the outfield.

Chorlton did not take the Hornsby’s reprimand well. He cursed and argued with the famous manager, then exited the dugout and went into the Rainiers clubhouse. Hornsby had a standing rule that players remain on the bench until the final out.

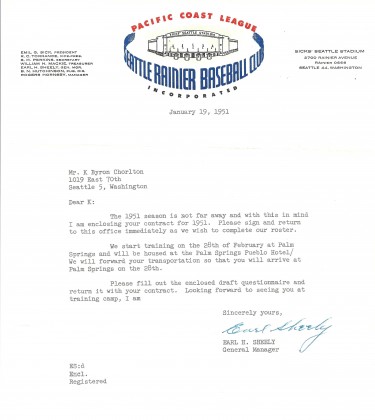

“I knew about the rule,” Chorlton said later. “I went in and asked Earl Sheely, the general manager, if he couldn’t help me with my problem. He did. The next day, I was in Tacoma.”

Hornsby had not only ordered Chorlton’s banishment to Tacoma of the Western International League, he carried his grudge to the point of making sure that Chorlton wouldn’t rise above the low minor leagues again any time soon. Then, as now, as Watson pointed out in the newspaper, “they call this blackballing.” (see Wayback Machine: Rajah, Rivera, ’51 Rainiers)

“You don’t cuss out a Hall of Famer,” admitted Chorlton, who did not receive another shot with the Rainiers until Hornsby left the franchise a year later.

Watson considered Hornsby’s deliberate humiliation of Chorlton a greater baseball sin than Chorlton’s missed fly ball and dugout rant, and said so in the next day’s newspaper in a colorful skewering of the famous manager.

After the article appeared, Watson was asked if his 1,000-word diatribe had angered the misanthropic Hornsby.

“I don’t really know,” Watson replied. “Hornsby treats me so bad when he’s in a good mood, I couldn’t tell the difference.”

Chorlton’s run-in with Hornsby proved to have an extremely negative effect on the player’s career. The Rainiers traded him out of Tacoma within weeks of the argument and he spent most of the next four years shuttling around the Western International League, mostly between Vancouver and Victoria, where he did a reasonably good job hitting WIL pitching.

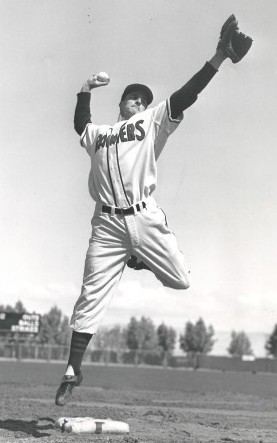

Such an athletic fate was not what K Chorlton watchers had expected from a young man considered a legitimate major league prospect and once crowned “the fastest man in the Pacific Coast League.”

Born Oct. 26, 1928 in Seattle, K Byron Chorlton first lifted public eyebrows during his sophomore year at Roosevelt High School, and it wasn’t only his athletic prowess that came under discussion. To start with, there was his unusual first name, simply “K”.

Chorlton received the abbreviated tag from his parents via a second cousin, an FBI agent who had been christened “Kermit,” a name Kermit apparently loathed. Kermit retaliated by changing “Kermit” to “K,” no period. Apparently impressed, Chorlton’s parents passed the single initial along to their son.

“For some reason, they liked it,” Chorlton said. “It was good when I was a pitcher, but not so good as a hitter.”

Chorlton idled away much of his youth playing pepper with his father, James, a chiropractor, and practicing tap dancing routines with his sister Ffolliott, named after her mother and known to her friends as “Fluff.” Both the pepper games and tap dancing routines later factored heavily in K Chorlton’s life.

On April 4, 1944, only weeks after his mid-term enrollment at Roosevelt, Chorlton, a 15-year-old sophomore, made his first pitching appearance for the Roughriders. He fired a no-hitter against Cleveland High, striking out 14 while walking just three.

“How do you prep diamond fans like those kind of apples?” asked Jack Fraser in The Seattle Times.

As a junior, Chorlton defeated the Ballard Beavers May 22, 1945, with a walk-off home run in a first-place showdown and pitched his team past Queen Anne High in the city championship game.

A year later, Chorlton combined with a teammate on another no-hitter.

Chorlton was almost as good at basketball as he was at baseball. In 1946, he helped Roosevelt to a 17-0 season and a state championship. The Teddies went 15-2 the following season.

Chorlton, 6-foot-3 and 180 pounds, made All-City and All-State in baseball and basketball, multiple times.

So good was Chorlton, who spent his summers in those years playing baseball for the semipro Mount Vernon Milkmaids, that several Seattle sports writers, using a phrase apparently coined by Jack Fraser in The Times, frequently began stories with “K (Frank Merriwell) Chorlton of Roosevelt High . . .”

They referred, of course, to the juvenile fictional character created by Burt Standish who excelled in a wide variety of sports at Yale while solving mysteries and righting wrongs.

Years after Fraser elevated Chorlton to near-mythic status with his Frank Merriwell reference, Dan Raley, in his splendid “Where Are They Now” series for the old Seattle Post-Intelligencer, wrote:

“While some questioned the Post-Intelligencer for recently singling out Chorlton as Roosevelt High School’s greatest all-time athlete, his reputation is irrefutable, his magic intact. For six decades, he has been a movie waiting to happen, though, in this case, Robert Redford would have had to call it, ‘The Natural Times Three.'”

Chorlton also played for the Roosevelt football team, but his father, fearing injury that might compromise a promising baseball career, refused to allow his son to take part in contact.

So K handled punting duties with considerable distinction. In 1946, he scored touchdowns in consecutive weeks, one following a bad snap, the other on a fake punt. The latter play resulted in a 31-yard scoring romp that beat West Seattle 6-0.

The newspapers selected Chorlton as an All-City, honorable-mention running back based on two explosive plays.

In Chorlton’s junior year, the Roosevelt track team challenged the baseball team to a series of races. Baseball player Chorlton won the 100- and 200-yard dashes.

K (Frank Merriwell/Roy Hobbs) Chorlton had it all going for him, as he admitted to Raley in Raley’s “Where Are They Now” article published June 8, 2004.

“I was a shooting star,” Chorlton told Raley.

He sure was. In his senior year, Chorlton was selected to play in the second annual Hearst Sandlot Classic, an all-star game featuring the United States All-Stars vs. the New York All-Stars sponsored by Hearst newspapers at the Polo Grounds.

The game drew 31,223, Chorlton doubled, stole a base and scored a run for the United States All-Stars and met Joe DiMaggio of the Yankees.

The meeting occurred when Chorlton was invited to Yankee Stadium for a private workout. After catching flies in the outfield, he encountered DiMaggio, who offered some advice on how to get a good jump on the ball.

“I admire you so much,” Chorlton told the Yankee Clipper.

“I wish I had your legs,” said DiMaggio, then recovering from a knee injury.

Chorlton also met Honus Wagner, one of his All-Star coaches, and Babe Ruth, who served as honorary chairman of the event, and left New York dreaming of the day he would play in the majors.

Several teams expressed interest, including the Yankees, Boston Braves, Detroit Tigers, Brooklyn Dodgers, New York Giants and Washington Senators.

But after his high school graduation, Chorlton accepted a combined basketball-baseball scholarship to the University of Washington, motivated in part because he did not want to venture far away from his childhood sweetheart and eventual wife, Diane.

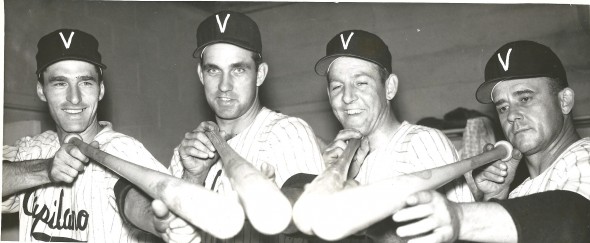

Chorlton played both sports for three years, playing guard on Art McLarney’s basketball team and in the outfield, also for McClarney, a double head coach. He made All-Coast in baseball as a junior before signing with the PCL’s Seattle Rainiers, who lured him with $10,000 (in 2001, he was named to Washington’s All-Century team).

Chorlton was also influenced to sign with the Rainiers due to the success of Sammy White, who joined the Rainiers as his own stepping stone to the majors after playing basketball and baseball at Washington with Chorlton.

“He was one of the players I signed after World War II out of Roosevelt High School,” then-Rainiers president Torchy Torrance wrote in his 1988 autobiography Torchy! He had lots of speed, a good arm and could hit pretty well. He went to our farm club in Vancouver first and then was with the Rainiers under Paul Richards (1950).” (see Wayback Machine: Roscoe ‘Torchy’ Torrance).

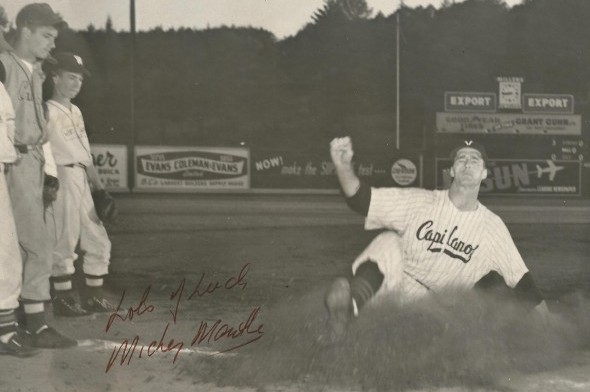

That began the process of K Chorlton learning how to become a professional. In 1949, he seemed to be getting the hang of it when, in 71 games for the Class B Capilanos, he hit .287 with five home runs and 15 doubles.

Under Richards, a one-year manager in 1950, Chorlton hit just .232 in 77 games, but batted .333 in 60 games for the Class B Victoria Athletics, also of the Western International League.

In the first 22 games of the 1951 season, Chorlton started to demonstrate he could hit at the AAA PCL level, batting .294 with a .415 on-base percentage. But then came that line drive to left field that changed K Chorlton’s athletic life.

“When Rogers Hornsby took over, he put Chorlton in left field and his first chance was a sinking line drive which hit the heel of his glove and popped out,” Torrance wrote in his bio. “Hornsby pulled him right in the middle of the inning, which was a real blow to Chorlton’s morale.

“After that he was shuttled between Vancouver and the Rainiers under (Bill) Sweeney and (Jerry) Priddy, but I think what happened with Hornsby stuck with him and really discouraged him. I still thought he had what it took to become a major leaguer, but . . . ”

But Frank Merriwell/Roy Hobbs advanced no further. When Sweeney took over as manager in the spring of 1952, Chorlton was among those present at the club’s Palm Springs training camp. He showed enough to warrant a job for the entire year, but only went to bat 156 times, hitting .218.

He returned to the Rainiers in 1953, but his ability was not sufficient in Sweeney’s estimation to stick with the club. Sweeney informed Chorlton that he would be wise to get out of baseball rather than squander his life in A or B leagues.

However, Chorlton stuck with it, so the Rainiers sold him to Vancouver, and then repurchased him near the end of the season after he batted .267 for the Capilanos.

Priddy took over as manager in 1954 and could not find room for Chorlton and sold him back to Vancouver, where he had the best – and last – season of his professional career, hitting .349 with 16 homers and 74 RBIs.

Chorlton had a chance to return to the Rainiers in mid-1954, but declined the offer. He had, he told The Vancouver Sun, more fun playing in Vancouver and he also made more money in Class A than he would make in the PCL.

“Chorlton’s career in Vancouver spanned the move to spanking-new Capilano Stadium midway through the 1951 season,” wrote British Columbia baseball researcher Tom Hawthorn. “With his speed, Chorlton often batted leadoff for Vancouver. He became a fan favorite.”

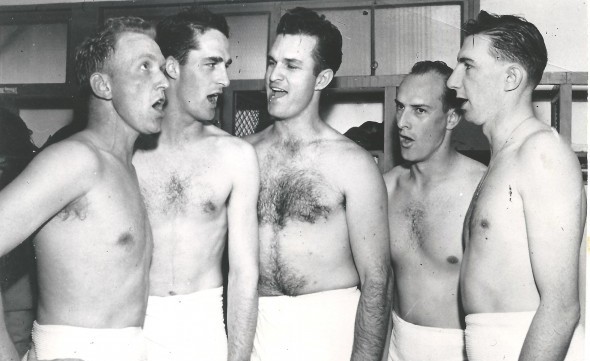

His popularity not only stemmed from his play. It was also the result of the fact that Chorlton, who tap danced as a kid, was an accomplished amateur singer and actor, who often entertained Capilanos fans with his barbershop quartet.

“One of the prettiest local sights on a summer’s evening is that of Chorlton scudding around the basepaths out at the ballpark,” Eric Whitehead wrote in The Province. “Graceful as a young gazelle and about as speedy, Chorlton would rate a quick boost up the ladder if he could only develop the elusive knack of getting on the basepaths more often.”

Somewhat reluctantly, but after enduring a sore arm and broken ankle in his last two seasons, Chorlton retired on the eve of the 1955 season. During his minor league career he averaged .304. No telling what he might have done as a baseball player if Rogers Hornsby hadn’t wrecked his confidence.

Chorlton, named to the Roosevelt High Hall of Fame in 2005, went into the wholesale furniture business after baseball and later became a sales executive for a company, the Ferrous Corp., which sold fuel additives.

Active in the community, he served as president of the 101 Club at the Washington Athletic Club (his Rainiers jersey is still on display), involved himself with Seafair (in 1982, he was Hugh McElhenny’s “Prime Minister” when McElhenny presided over the summer celebration as “King Neptune”), and occasionally acted in local stage productions.

In 1959, for example, Chorlton played Dr. Woolley, medical chief staff, in You’re The Doctor, in a fundraiser for Overlake Memorial Hospital. Chorlton acted in several benefit plays for the hospital.

K died March 17, 2009 in Bellevue of pneumonia. He left behind four children, 10 grandchildren and his sister, Ffolliott, who, as Fluff LeCoque, worked as a dancer for Liberace’s show on the Las Vegas Strip in 1947.

————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

2 Comments

What’s up with the ridiculous posing, was this pretty common back then?

Extremely common.