By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

It’s a rare occurrence when a graduate of the University of Washington football program succeeds in the National Football League to a greater degree than he did as a Husky. Most notably, tackle Arnie Weinmeister had a World War II-interrupted career of no particular distinction at UW from 1942, ’46-47 and then proceeded to All-Pro recognition and a Hall of Fame salute following six seasons with the New York Giants.

Thirty years later, and although he led Washington to a 1978 Rose Bowl triumph over Michigan, Warren Moon provided little hint performing under Don James that he had a Pro Football Hall of Fame career in his future, especially after spending his first five years in the Canadian Football League. But Moon played 17 seasons with four NFL teams, threw for 49,325 yards and 291 touchdowns, and entered the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2006 on his first try.

Benjamin Franklin Davidson Jr. seemed an even less likely candidate for NFL stardom than either Weinmeister or Moon. He had no interest in high school football, never attended and rarely watched (on TV) football games while growing up, didn’t do much in the sport during two years at East Los Angeles Community College, and started only two games in two seasons at Washington, despite his stupendous physical stature, 6-foot-8, 275 pounds.

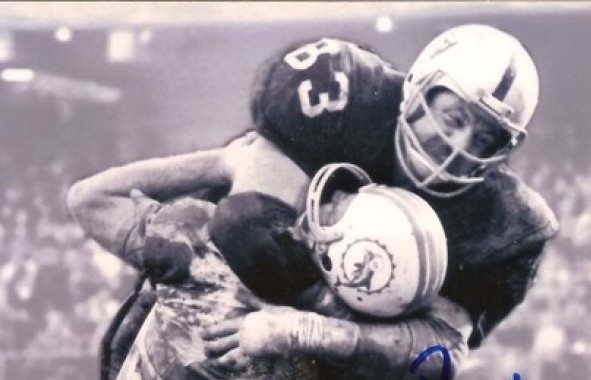

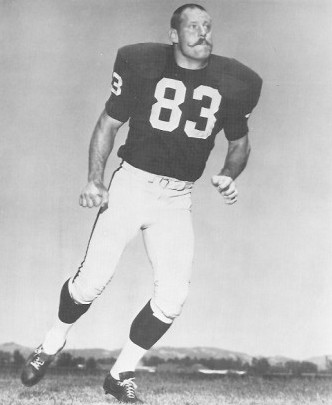

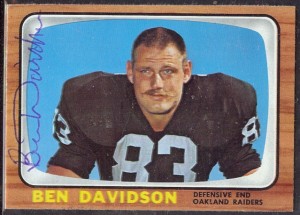

But Davidson constructed an 11-year career (1961-72) in the NFL with three franchises, notably the Oakland Raiders, earned three Pro Bowl invitations and made first-team All-Pro in 1967, thriving as a pass rusher and mustachioed renegade under head coach John Madden. Although he developed into an outstanding player, Davidson actually became more famous during his post-football life.

“There’s no telling what I would have done if it hadn’t been for football,” Davidson told an interviewer in 1995. “But it became the perfect life for me.”

The son of a 6-foot-4 L.A. cop, Benjamin Franklin Davidson Sr., and a 5-foot-10 librarian, Avis, Ben Jr. was born in Los Angeles June 14, 1940. When he received his first driver’s license at age 16, Davidson was already 6-7 and weighed 215 pounds. Since Woodrow Wilson High, in the El Sereno neighborhood, did not have a uniform that would fit him, he went out for basketball and track, becoming a pretty decent hurdler, high jumper and shot-putter.

Davidson intended to pursue basketball and track at East Los Angeles Community College, but a football coach spotted him and asked him to join the team. That was in 1957.

“I just decided that I’d try it,” Davidson told The Los Angeles Times. “I didn’t know the positions. I knew the center was probably in the middle, but I’d only been to one or two games and I never really paid much attention to it. I had no idea what kind of stance to get into. That was a major project. The coach had me so fixated on getting a good stance that I’d be looking down at my legs, trying to make sure everything was right, and they’d snap the ball.

“I was a 60-minute man during my first season at East L.A.,” said Davidson, whose teammate that year, George Fleming, became a co-Rose Bowl MVP at Washington (1960). “Sixty minutes for the whole season, that is.”

One incident pretty much convinced Davidson that football was his game. An opponent clipped him from behind, and Davidson retaliated by reaching into the miscreant’s helmet and gouging his eye.

“He screamed and ran off the field,” Davidson said. “That’s when the light bulb went on in my head and I said, ‘I can do this.’ I actually think that’s when I became a Raider.”

The next year, Davidson started every game and attracted attention from major college recruiters up and down the West Coast. One of them, USC assistant coach Al Davis, made it his mission to make Davidson a Trojan. But Norm Pollom, a University of Washington assistant and later a long-time NFL scouting executive with the L.A. Rams and Buffalo Bills under Chuck Knox, managed to steer Davidson to the Huskies.

He arrived on the UW campus as a “sure thing” – eventually.

“It’s a long jump from one season of regular play at the junior college level to contention on a major college team,” head coach Jim Owens said after watching Davidson practice a few times. “Defensively, Davidson is a stubborn obstacle because of his size. He rarely can be moved, but he can be fooled. Good thing is, he’s a fast learner.”

During one of his initial practices at Washington, Davidson, in a one-on-one drill, literally picked up the man trying to block him and threw the poor bloke at the ball carrier.

“I’m not sure it’s legal, but I like his ingenuity,” said Owens.

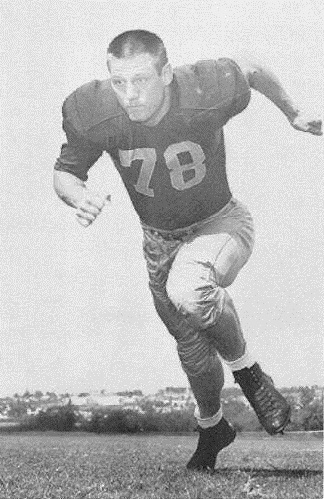

Davidson began a two-year stay with the Huskies as a fourth-string defensive tackle and ultimately worked his way up to second-string tight end on a line that included All-Coast selections Roy McKasson and Chuck Allen, and to second-string defensive end.

Davidson ran track and was Washington’s intramural champion in both the low and high events and a good enough wrestler that he qualified to compete in the 1960 U.S. Olympic Trials in Ames, IA. He won his first match, but was eliminated in the second by Dale Lewis of Oklahoma, the defending NCAA champion.

Contributing where he could in Owens’ one-platoon system, Davidson played a part in two of Washington’s best seasons. The 1959 club went 10-1, losing only to USC, and splattered Wisconsin 44-8 in the Rose Bowl. The 1960 team also went 10-1, losing by a point (15-14) to Navy, and beat Minnesota 17-7 in Pasadena.

Those Owens clubs, the first to win Rose Bowls for Washington, included some of the most storied names in Husky history – Bob Schloredt, Don McKeta, Roy McKasson, George Fleming — but a surprisingly small number played professionally.

Guard Chuck Allen spent 11 years (1961-72) with the Chargers, Steelers and Eagles), earning All-Pro status, and end Lee Folkins had a four-year run (1961-65) with the Packers, Cowboys and Steelers). Davidson, though, honorable mention All-Coast even though he was a substitute, was selected above all other Huskies in the 1961 NFL draft.

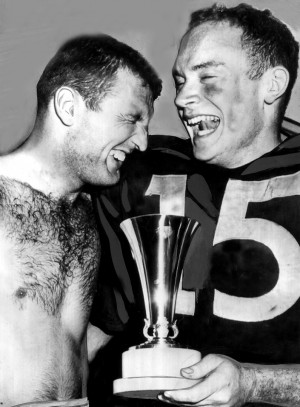

The New York Giants tabbed him in the fourth round, but traded him to the Packers during training camp. As he had with the Huskies, Davidson played a limited role on the Green Bay team that won the 1961 NFL title (he used his $5,000 winner’s share to buy a Seattle apartment complex).

The Packers traded Davidson to Washington for a fifth-round draft choice, and he spent two undistinguished years with the Redskins before being cut, a move that might have ended his career if Al Davis, the former USC assistant, hadn’t been coaching the Oakland Raiders. Davis claimed Davidson off waivers, his first order that Davidson shave off his full-length beard. Davidson balked, and he and Davis compromised on a handlebar mustache that became Davidson’s trademark.

“Ben Davidson is the best physical specimen I’d ever seen,” former Packers guard Jerry Kramer told the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel. “Six-foot-8, 278 pounds. Big shoulders. Decent speed. But he wasn’t real aggressive and not quick with lateral movement. I’m not sure what all happened in Oakland, but he became a pretty darn good football player.”

In fact, Davidson flourished under Davis and, later, Madden. Between 1964-72, Davidson played 110 games with 70 starts, made three AFL All-Star teams and was part of the league merger in 1970.

In those years, the Raiders had a mystique and Davidson was a big part of it.

“Opposing players knew that when they played the Raiders, they were going to lose, to begin with, and get severely pummeled,” said Davidson.

Davidson had several headline-making moments, among them a game Nov. 1, 1970 against the Kansas City Chiefs. The Chiefs led 17–14 late in the fourth quarter when a long run for a first down by Chiefs quarterback Len Dawson set up Kansas City for victory in the final minute. As Dawson lay on the ground after his run, Davidson speared him, provoking Chiefs’ receiver Otis Taylor to attack Davidson.

After an obligatory brawl, officials called offsetting penalties, nullifying Dawson’s first down under rules in effect at the time. The Chiefs punted, and the Raiders tied the game on George Blanda’s 48-yard field goal with eight seconds to play.

Davidson’s play not only cost the Kansas City a win, but gave Oakland the AFC West title with a record of 8-4-2. Kansas City finished 7-5-2 and out of the playoffs. After the season, the NFL changed its rules regarding personal fouls, separating them into ones called during the play, and ones called after the play.

Davidson relished roughing up people, but his reputation as the most intimidating, physical player in the league got started due to an incident in which he was innocent. During a 1967 game between Oakland and the New York Jets, a crush of Raiders swarmed Joe Namath, knocked the quarterback’s helmet off and fractured his cheekbone. Davidson got credit for the hit, although teammate Ike Lassiter was responsible. Lassiter refused to talk about the play and Davidson never denied breaking Namath’s cheekbone.

Davidson later said that if he hadn’t received so much publicity over the incident, he probably wouldn’t have enjoyed the post-football career that he did.

After Davidson played a final season (1974) in the World Football League for the Portland Storm (roster included ex-Husky linebacker Rick Redman and ex-WSU CB Clancy Williams), he turned his full attention to acting. Davidson had already appeared in two major films: Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H (1970), in which he played in a football game for the 4077th, and Behind the Green Door (1972), the landmark porn film starring Marilyn Chambers.

Davidson subsequently landed roles in The Black Six (1974), about an outlaw biker gang; Conan The Barbarian (1982) and Necessary Roughness (1991). He appeared in the 1976 short-lived TV show Ball Four, the 1984 TV Series Goldie and the Bears. Davidson also turned up in countless TV shows, including Charlie’s Angels, Fantasy Island, Dukes of Hazzard, Happy Days and CHiPs.

Davidson’s biggest role, though, came when he played himself in 27 commercials during the 1980s for Miller Lite beer ads featuring John Madden and Rodney Dangerfield. They featured a variety of ex-jocks, including Bubba Smith, Dick Butkus and Tommy Heinsohn.

The long-running campaign included hilarious arguments between George Steinbrenner and Billy Martin, Madden bursting through a wall, and Bob Uecker being Bob Uecker. Davidson’s wacky sense of humor made him a natural TV pitchman, and he traveled extensively to corporate outings to promote the beer.

“I was a geography major in college, so I love to travel,” Davidson told the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel. “Greenland, Guam, Korea, Panama, Honduras — you name it. We signed autographs, met people and drank beer. I made more money doing that than playing pro football.”

Davidson pitched beer in every state except Delaware and in a long line of foreign countries, turning his paid appearances at corporate outings into a second career.

“It was a lot of fun. The company, to its credit, allowed time for some infantile horseplay. That was reflected in the commercials,” said Davidson. “We were having fun.

“I’m not Catholic,” Davidson told The Los Angeles Times in 2010, “but sometimes when I say, ‘Lite beer,’ I make the sign of a cross. If I could have designed a job for myself post-football, it would have been exactly what I did. I hate to say this for print, but I’m 70 years old and I’ve never had a real job.”

But he had perfect timing. With the Packers, he appeared in the 1961 NFL championship game. With the Raiders, he played in Super Bowl II. Four of the Oakland teams he played for won division titles.

“He was a tough, gutsy ballplayer, team oriented, with enough meanness in him to be feared and enough talent to be effective,” former Raiders teammate Tom Flores told the Associated Press shortly after Davidson died July 2, 2012.

Prostate cancer got Big Ben, a San Diego retiree, at 72.

————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

2 Comments

Thanks Mr. Eskenazi good memories going back to the Huskies and Raiders of my youth. I got to meet many of the players/coaches mentioned in your article.

Big Ben and Al Lassiter and Joe Namath in epic battles; great fun.

Growing up I enjoyed Ben’s Hollywood career more than his football career. (He was a Raider after all) But I’ve still enjoyed reading and hearing of his career(s) over the years. You don’t see TV Shows like what he appeared in anymore. Too many reality TV shows and reality based police dramas. I wish Miller would revisit their retired jocks marketing campaign.

Seeing film of him in his playing days I wish the Hawks had him right now! Bet the Raiders thinks the same.