By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

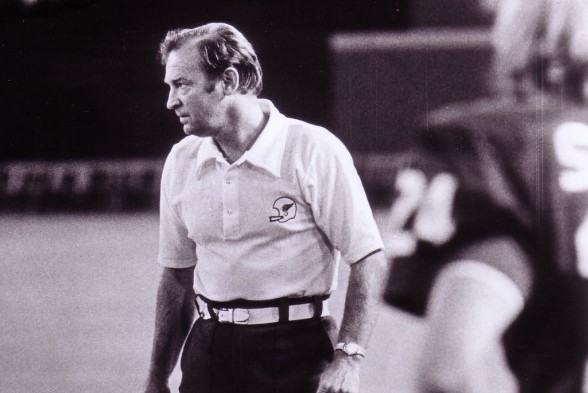

It’s been five years since Don Coryell’s name first appeared on the Pro Football Hall of Fame ballot, and the Washington state native is again a semifinalist (finalists will be announced next week). To the great consternation of the legion of Hall of Famers who have long championed his cause, Coryell’s induction is way past due and an oversight, in their collective mind, that defies logic.

They point to his exemplary coaching record, to the creative offensive schemes he pioneered that are still widespread throughout the NFL, to the manner in which those innovations compelled defenses to innovate in order to effectively compete against him, and to the array of coaches who learned under him and succeeded after they left him.

Critics of Coryell’s HOF candidacy fixate on the fact that neither of the franchises he coached, the St. Louis Cardinals (1973-77) and San Diego Chargers (1978-86), won a Super Bowl, as if to suggest that is, or should be, the defining factor in assessing a coach’s worthiness.

Critics also argue that Coryell, while turning around moribund operations in St. Louis and San Diego, produced division winners but never elite teams, and that his “innovations” were more the result of his taking advantage of sweeping rules changes in 1978 that unleashed the NFL’s live-ball era.

Most coaches saddled with tepid postseason records never get to the Hall of Fame debate stage. But in his case, the indisputable – and complicating — fact is that few men influenced the development of pro football, particularly the modern passing game, more than Coryell.

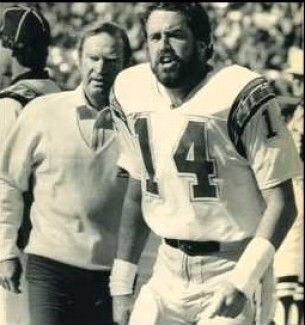

“Who contributed more in the last 40 years than Coryell? Nobody,” said his former quarterback, Hall of Famer Dan Fouts, who starred at the University of Oregon and for the San Diego Chargers. “Who influenced more the way the game is played on both sides of the ball? Nobody. The NFL is the most successful sports enterprise in our country, and I would bet the world. It’s mind boggling that Coryell’s influence isn’t recognized.”

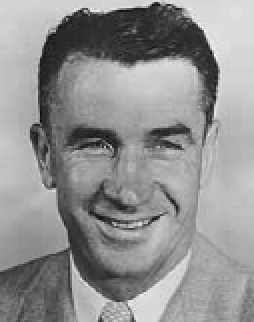

Born in Seattle Oct. 17, 1924, one of four sons of George and Julia Coryell, Coryell grew up in a middle-class neighborhood just north of the city, summered on Vashon Island, graduated from the old Lincoln High School and enlisted in the Army in 1943, serving 3½ years as a paratrooper during World War II.

He enrolled at the University of Washington as a 24-year-old in 1948 and spent, as a halfback/defensive back, three mostly anonymous years from 1949-51 (the Don Heinrich-Hugh McElhenny era), earning but a single letter (1949), his lack of size limiting his playing opportunities under head coach Howie Odell.

After leaving UW with bachelor and master’s degrees, Coryell launched his 29-year coaching odyssey, starting at the prep level in Hawaii. From there, he whisked through the University of British Columbia and Wenatchee Valley College before serving a stint with a military team at Fort Ord, CA.

Coryell landed his first head coaching job at Whittier College in Orange County CA., in 1957 and won two conference titles in three years while pioneering the I-formation. That brought Coryell to the attention of USC’s John McKay, who hired Coryell as an assistant in 1960. McKay quickly adopted Coryell’s I-formation and churned out a string of Heisman Trophy winners with it.

In 1961, Division II San Diego State brought Coryell aboard to turn around a program that couldn’t hold its own in recruiting wars with other California colleges of its size, much less with USC and UCLA. To stock the Aztecs’ roster, Coryell mainly relied on junior college transfers.

Coryell discovered he could lure to San Diego State many more skill players than the quality of lineman that make major programs elite. That became the genesis of one of Coryell’s major contributions to the game, his creative offensive schemes.

Coryell gradually moved away from the I in favor of a passing attack that not only spread the field, but lengthened it. San Diego State didn’t have the athletes to win 7-0 or 10-7 games, or any contest conducted in a trench. But with the skill players Coryell deployed, and the plays he conjured, the Aztecs could win shootouts, and they won a ton of those. In 1969 alone, the Aztecs scored 50 or more points five times.

Coryell coached the Aztecs for 12 years (1961-72), amassing a stunning record of 104-19-2. He produced three undefeated seasons – 1966, 1968, 1969 – and won three bowl games. NFL teams drafted 42 of Coryell’s players, and two of his assistants, John Madden and Joe Gibbs, both of whom worked under Coryell from 1964-66, became Super Bowl-winning head coaches and inductees into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

When Coryell arrived in St. Louis in 1973, one dismal fact stood out: The Cardinals had been absent from the playoffs for 26 years. But under Coryell, the Cardinals posted three consecutive seasons (1974-76) with double-digit victories and won two division titles (1974-75). Those were the only division crowns the Cardinals won during their otherwise feeble residency under the Arch.

Coryell’s 1975 Cardinals, featuring Seattle native Terry Metcalf, became his signature St. Louis team. The “Cardiac Cardinals” went 11-3, winning seven times in the game’s final minute. When the Cardinals refused to re-sign Metcalf after the 1977 season, Coryell also left. The Cardinals didn’t reach double figures in wins again for 33 years.

Coryell signed with the Chargers Sept. 25, 1978, inheriting from Tommy Prothro a team that went 13 years without a playoff appearance and started the 1978 campaign 1-3. Under Coryell, the Chargers started 8-4, finishing 9-7.

Over the next eight years, Coryell cemented his status as the primary father of the modern passing game. His Chargers evolved into “Air Coryell,” playing some of the most exciting football the NFL has witnessed, a brand that featured long passes, quick-strike touchdowns, points galore and a whole lot of entertainment.

Led by Fouts, the Chargers topped the NFL in passing yards five straight seasons from 1978 to 1983 and again in 1985. San Diego, which also led the league in scoring in 1981 and 1982, averaged an astonishing 28 points per game during a 57-game stretch from 1979 through 1982.

Coryell led the Chargers to division titles in 1979, 1980 and 1981 and to the playoffs every year from 1979-82 after they had not been to the postseason since 1965. While Coryell’s teams never won the Super Bowl, they twice made it as far as the AFC Championship game and won the most famous playoff contest in history, a 41-38 overtime thriller over the Miami Dolphins that losing coach Don Shula described as “the best game ever played.”

Coryell’s success stemmed from his principal innovation, the passing tree, which provided the quarterback with a progression of reads.

“He (Coryell) wanted to spread the field and throw the football, looking for that mismatch,” his former San Diego tight end, Kellen Winslow, said in the aftermath of Coryell’s death in July 2010.

“It was an attitude of attack,” Fouts added. “We were going to attack every part of that field — width, length — and then we were going to attack every weakness in that defense. It’s like fast breaks in basketball. Three-on-two, then it comes down to a two-on-one, and then it’s a one-on-none. Throw the ball to the one-on-none. It was the attitude of, ‘Look for the bomb first, and then work your way back to the line of scrimmage.'”

Jerry Magee covered the Chargers for the San Diego Union and later the San Diego Union Tribune, witnessing every game of the Coryell era.

“His emphasis on passing, the use of motion, the many packages, some with four receivers, some with three, some with two running backs, some with one, some with none, became his trademark,” said Magee.

“Anyone wishing to weigh Coryell’s qualifications (for the Pro Football Hall of Fame) need only witness what is occurring on NFL fields, in how teams operate their passing games, from a variety of packages, with the routes assigned numbers and branching off as if from a tree. Coryell introduced this practice.”

While Bill Walsh is credited with popularizing the West Coast offense with the Joe Montana-led San Francisco 49ers, all Walsh did was ape what he had seen Coryell do at San Diego State and later with the Chargers.

“They call it the West Coast offense because San Francisco won Super Bowls with it,” said Winslow. “But it was only a variation of what we did in San Diego. When the Rams won their Super Bowl (1999), it was the same offense, same terminology. Fans can’t watch the NFL today and not see Coryell’s influence. And that’s why he should be in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, as an innovator and as a contributor. You can’t put a dollar figure on his value to professional football.”

Now with CBS, Fouts doesn’t have a Hall of Fame vote but has a message for those who do:

“After 1978, the passing yardage throughout the NFL took off and Coryell’s team led the way,” said Fouts, a first-ballot Hall of Famer in 1993. “We led the NFL in passing five straight years in total yardage. The next year we finished second and the following year we finished first. So six out of seven years the Chargers led the NFL in passing yardage.

“You can go back and look at any category of statistic and you will not see a stretch of seasons in any category that one team dominated like that.

“I’d also ask (Hall of Fame) voters, how did we get to this point defensively, where you’re seeing extra defensive backs and pass-rush specialists being drafted No. 1? That will take you back to that 1978 period when the game changed. Who dominated the passing game in that period? Where did today’s defenses originate? You can trace it right back to Don Coryell’s desk.”

To the criticism that Coryell didn’t win a Super Bowl, Fouts said, “First of all, winning the Super Bowl is apparently not a criteria for putting coaches in the Hall of Fame. George Siefert won two, Tom Flores won two, Brian Billick (and Mike Holmgren) won one and they never get a mention. George Allen didn’t win a Super Bowl and he’s in the Hall of Fame. Obviously, the goal is to win, but look at Coryell’s influence and the contribution he made to the most popular sport in the country.

“Whether he won Super Bowls or not, there are plenty of coaches who benefited from his system — Jimmy Johnson and Barry Switzer with the Cowboys. They used Coryell’s system and so did Mike Martz in St. Louis. Shouldn’t the man who got these men to the Super Bowl and won it be considered a contributor to the great game of football?

“Okay, the Super Bowl is big. But I’ve talked to writers and I ask, ‘Who won Super Bowl 27? Who won Super Bowl 13? Who won Super Bowl 40?’ They have no idea. But if I ask, ‘How about the San Diego-Miami overtime game?’ They always say it was greatest game ever played. Okay, and who was the coach? And Coryell beat a coach that’s in the Hall of Fame, Don Shula.

“How did I get in the Hall of Fame on the first ballot? How did Charlie Joiner get in? How did Kellen Winslow get in? We never won a Super Bowl. But we benefited from Coryell’s system. And that’s not easy for a Duck to say about a Husky.

“Sure, Don tried to win the Super Bowl, but there were a lot of things out of his control (draft, trades). In 1979, the Chargers – and no team has ever done this — put three starting defensive linemen in the Pro Powl. The Chargers had 60 sacks – SIXTY! – that year, Gary Johnson, Louie Kelcher and Fred Dean. You know what the owner did after that season? He fired our defensive coordinator!

“So you change the coordinator and what does he do? He changes the system and the players to fit his system and so you have a setback. You know where Johnson, Kelcher and Dean ended up? In San Francisco. And they all earned Super Bowl rings. Bill Walsh had spent time in San Diego in 1976 and he coveted those guys.”

Added Martz, architect of the “Greatest Show on Turf,” in an interview with the Pro Football Hall of Fame: “People talk about the West Coast offense, but Don started it and kept updating it. You look around the NFL, and so many teams are running a version of the Coryell offense. Coaches have added their own touches, but it’s still Coryell’s offense. He has disciples all over the league. He changed the game.”

Certainly Coryell took advantage of rules changes in 1978 that provided coaches the opportunity to open up their offenses. But Coryell exploited the new rules to a far greater degree than anyone. He had the perfect compliment of offensive players to do it.

In 1979, Fouts became the second player (following Joe Namath) to pass for 4,000 yards in a season. He set another yardage record in 1980, and another in 1981. In 1982, in a season shortened to nine games because of a strike, Fouts averaged 320 passing yards and later became one of the few modern-era quarterbacks to make the Hall of Fame without winning a Super Bowl.

Winslow might not have made it to Canton if Coryell hadn’t used him primarily as a receiver rather than as a blocker. But Coryell was astute enough to recognize that, “If we’re asking Kellen to block a defensive end and not catch passes, I’m not a very good coach.”

“Look at the tight ends today,” said Fouts. “You can trace the Rob Gronkowskis and Jimmy Grahams and Antonio Gates and Tony Gonzalez and all the great ones back to Kellen Winslow. He had his hand on the ground sometimes, but he was in motion, he was on the wing. Other coaches suddenly knew they had to get somebody like that.

“It goes back even before Winslow to Jackie Smith, who was in St. Louis when Coryell was there. John Mackey was maybe the first, but there was such a gap between Mackey and Jackie Smith and then to Winslow. But there was nobody else to compare to those three. After Winslow, everybody said we’ve got to get a tight end that we can put out wide and create an instant mismatch. That’s what Coryell did.”

In addition to Fouts and Winslow, Coryell coached running backs Chuck Muncie, James Brooks and Lionel James, and receivers John Jefferson, Joiner and Wes Chandler.

Jefferson is a great example of Coryell’s handiwork: In the three years (1978-80) Jefferson played for Coryell, he had three 1,000-yard receiving seasons and scored 33 touchdowns. In the five seasons he played after leaving San Diego, Jefferson never had a 1,000-yard season and scored 11 touchdowns.

Muncie spent the first five years of his career in New Orleans, scoring 28 touchdowns in 59 games. Muncie joined “Air Coryell” at its apex in 1981 and scored 39 over the next three years. Joiner had four 1,000-yard years, all under Coryell.

The ultimate manifestation of Air Coryell occurred in that San Diego-Miami game Jan. 2, 1982. Coryell trotted out a 400-yard passer (Fouts, 433), a 100-yard rusher (Muncie, 120), and THREE 100-yard receivers (Winslow, 166; Joiner, 108; Chandler, 106).

The first former University of Washington player to coach in the NFL and the only coach to win more than 100 games at both the collegiate and professional levels, Coryell is a member of five Halls of Fame: College Football, San Diego State, Husky Fever, San Diego Chargers and State of Washington.

When Coryell missed out on Canton in 2010, former Colts head coach Tony Dungy, a candidate for induction this year, remarked, “If you talk about impact on the game, training other coaches – John Madden, Joe Gibbs, Bill Walsh, to name a few – and influencing how things are done, Don Coryell is probably right up there with Paul Brown. He was a genius.”

“In the offense we won the Super Bowl with in 1999, the foundation was Don Coryell,” former Rams head coach Dick Vermeil told the Pro Football Hall of Fame. “The route philosophies, the vertical passing game, everything stemmed from the founder, Don Coryell. The genius.”

After Coryell’s funeral in San Diego in 2010, Madden said, “You know, I’m sitting down there in front, and next to me is Joe Gibbs, and next to him is Dan Fouts, and the three of us are in the Hall of Fame because of Don Coryell.”

Madden and Gibbs are the most prominent members of Coryell’s coaching tree. Madden won a Super Bowl with Oakland and sports the second-best winning percentage in NFL history. Gibbs won three Super Bowls as Washington’s head coach.

Jim Hanifan, who worked under Coryell in St. Louis, is regarded as one of the best offensive line gurus in league history. Ernie Zampese, another Coryell protégé, taught Coryell’s offense to Norv Turner, who installed it in Dallas and used it to win three Super Bowls in the early 1990s.

If Troy Aikman hadn’t quarterbacked those three Dallas Super Bowl winners, he would not be in the Hall of Fame because he didn’t have traditional Hall of Fame numbers. Three rings, not stats, greased his entry into Canton.

In the 1960s, Martz watched Coryell conduct San Diego State practices. Years later, he brought his version of Coryell’s offense to St. Louis, creating an attack that saw the Rams score more than 500 points in three consecutive seasons (1999-01). St. Louis never would have enjoyed the “Greatest Show on Turf” without Martz, who learned its basics from Coryell.

Should Coryell, who finished with a career coaching record of 240-113-4 (.678) in 29 seasons, including 111-83-1 in 14 NFL campaigns, make it to the Hall of Fame, he would join Sid Gillman and Greasy Neale as the only coaches in the Pro Football Hall of Fame and College Football Foundation Hall of Fame.

He would also become the second man born in Washington to reach Canton as a coach. The only other is Spokane native Ray Flaherty (born Sept. 1, 1903) who won two NFL titles (1937, 1942) with the Sammy Baugh-led Washington Redskins.

“I’m passionate about it,” said Fouts, who champions Coryell’s cause at every opportunity. “Induction should be based on one’s contribution to this great game, and I can’t think of anyone who contributed more.”

————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

1 Comment

I loved watching his teams. Wether it was the Cardiac Cardinals or the full blown Air Coryell in San Diego, it was amazing to watch. It’s a crime he’s not in HOF