By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

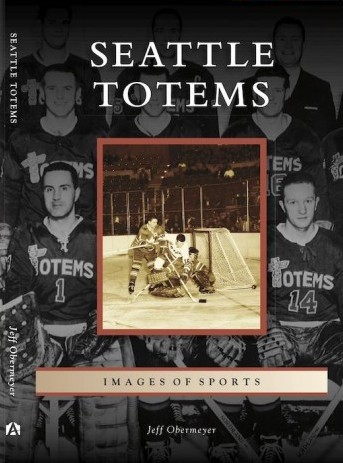

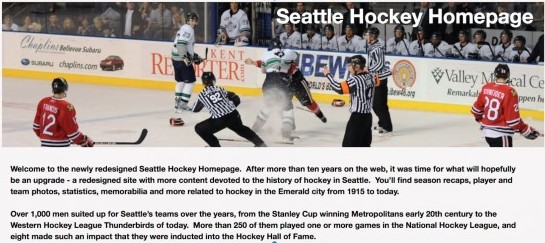

Starting with little more than a keen intellect and abounding curiosity, Jeff Obermeyer launched more than 20 years ago a personal research project focused on the history of professional hockey in Seattle. Now the acknowledged expert, Obermeyer operates the definitive website on the subject, seattlehockey.net, and is the author of three books, Hockey In Seattle (2004), Emerald Ice (2007) and Seattle Totems, the latter new in area bookstores and available on amazon.com.

For those whose grasp of Seattle’s pro hockey past is pretty much restricted to the recent aborted attempts by two groups of semi-local investors to acquire a National Hockey League franchise, the results of Jeff’s exhaustive probes will come as a fascinating revelation.

First, start by checking out the website, which delves into the principal teams and players in a timeline format, starting with the Seattle Metropolitans of the old Pacific Coast Hockey Association. He provides season-by-season summaries from the Mets’ inception (1915) through their demise (1924), which includes three appearances (and one victory in 1917) in the Stanley Cup finals.

From there, Obermeyer furnishes extensive background material on all of the franchises (and leagues) that followed the Metropolitans: Seattle Eskimos/Seahawks (1928-41), the City League (1920s-40s), Seattle Ironmen (1945-52), Seattle Bombers (1952-54), Seattle Americans (1955-58), Seattle Totems (1958-75), Seattle Breakers (1977-85) and Seattle Thunderbirds (1985-present).

Exposure to the T-Birds helped sparked his original interest in taking on what became a series of daunting research projects.

A native of Pennsylvania, Obermeyer didn’t pay much attention to the Philadelphia Flyers as a youth, but began to get hooked on the sport when he attended his first T-Birds game in 1989. Soon, he was following the Vancouver Canucks and watching Hockey Night in Canada. His interest in history developed when he looked up articles on newspaper microfilm that detailed a pair of games that the Seattle Totems played against the Russian national team, first in late 1972, the second in early 1974.

“That got me going down a very long path,” he said. “I started going to the library and printing out articles for every game from every season. It kind of built from there.”

By haunting card shows, garage sales and the like, Obermeyer began acquiring Thunderbirds memorabilia and eventually built a Totems collection of old programs, pucks, photos, etc. He launched seattlehockey.net to showcase it and has been adding to the site since. Now it’s crammed with information, classic photos dating to the Metropolitans, schedules, program covers, jerseys, memorable pucks, schedules and other memorabilia. It has evolved into the only web destination worth visiting on pro hockey in the area.

When Obermeyer began excavating Seattle’s hockey past, there was very little information available for public consumption. He made repeated visits to the main branch of the Seattle public library where, at his own time and expense, he spent countless hours in front of a microfilm reader. Eventually, he had a couple of bookshelves filled with articles on games and players.

On seattlehockey.net, you can find a wealth of statistical information dating to the Metropolitans, dozens of team photographs, stories and photos about the various arenas that housed the franchises, and a section devoted to the Seattle Hockey Hall of Fame.

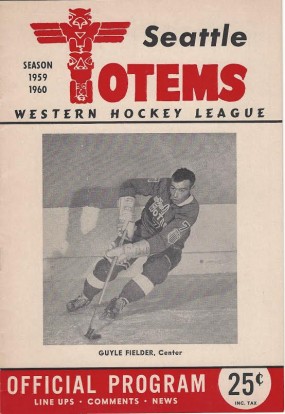

The exhaustive research and collecting resulted in his first book, the 128-page Hockey in Seattle. A history in photographs, it covers the period 1915-2004 and each major team that represented Seattle during that span is profiled, along with a chapter devoted exclusively to Guyle Fielder, the city’s all-time greatest player.

Three years later came Emerald Ice, a 280-page tome that breaks down each season in Seattle hockey history. Ninety of the 280 pages are devoted to year-by-year league standings, individual player statistics and significant records.

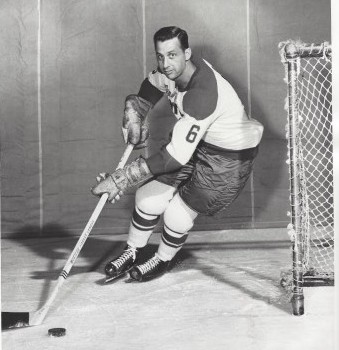

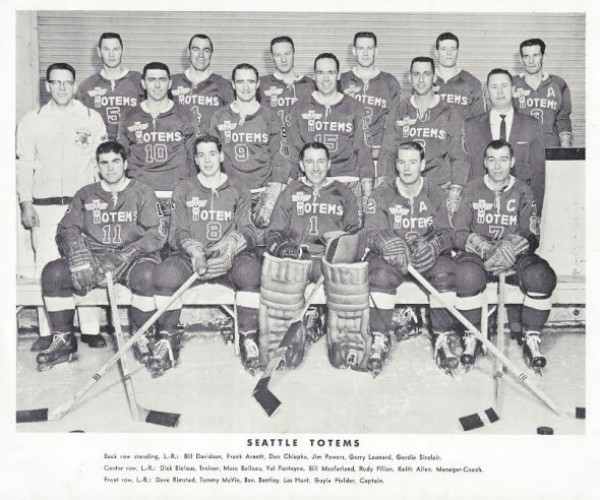

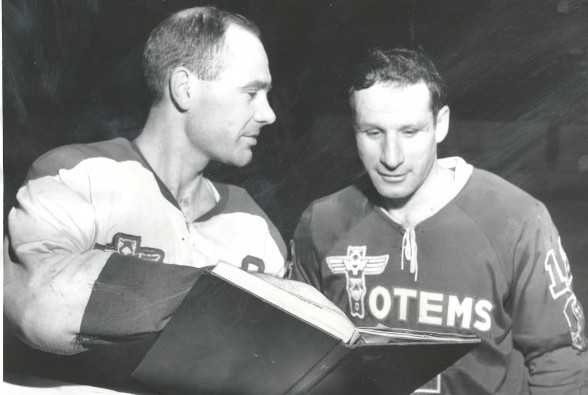

Through the course of his work, Obermeyer became acquainted with Fielder, a six-time Western Hockey League Most Valuable Player who starred for the Bombers (1953-54), Americans (1955-58) and Totems (1958-69). Fielder put him in touch Bill MacFarland, Val Fonteyne and many others who played with the Totems, which served as important background for Seattle Totems, a 128-page examination of that franchise that includes more than 200 rare photographs.

“Not only are there 205 photos in the book, but none of those photos appeared in my earlier book, Hockey in Seattle,” Obermeyer said. “So if someone has that book and is wondering how much of this is new material, not one single photo from Hockey in Seattle was reused in Seattle Totems.

Seattle Totems takes the reader through the entirety of the franchise with two important set ups. The first chapter – especially useful for anyone lacking a clue about Seattle’s hockey’s past – reviews the city’s early franchises, starting with the Metropolitans, and concludes with the Americans, the immediate forerunner of the Totems.

The second focuses primarily on Rudy Filion, an Ontario native who came to the Northwest as an amateur in 1947-48 and played for the Tacoma Rockets of the Pacific Coast Hockey League.

Filion donned an Ironmen uniform in 1948-49 and played 14 seasons in Seattle. He was a key component in the Totems’ 1959 WHL championship and, on March 11, 1960, on “Rudy Filion Night” at the Civic Arena, scored a hat trick in a 4-3 victory over the Spokane Comets.

“I put Rudy there because he bridges the gap from the Ironmen in the 1940s through the early years of the Totems,” Obermeyer said. “I got to know him more as a man than just Rudy Filion the hockey player. I found out the things that were important to him as a person, and I got to see what a good person he was. After the chapter on Rudy, I staggered the information, kind of alternating from a chapter on a specific player to a period of time.”

Included is a chapter on how the Totems emerged from the Americans and began the second “golden age” of Seattle hockey, the first from 1917-20 when the Metropolitans packed the downtown Seattle Ice Arena.

Rebranded and renamed “Totems” by a new ownership group for the 1958-59 season, the team appeared in five WHL finals, winning three titles, and five times featured the league MVP — Fielder four times and MacFarland once. Also during this period, the Totems moved from Mercer Arena to the Seattle Coliseum (now KeyArena).

With all of their championship runs, the Totems ranked as the No. 1 winter sports ticket in Seattle through most of the 1960s with Fielder the principal star.

“Guyle was in Seattle for a really long time,” Obermeyer said. “He won six MVP awards, won the scoring championship a million times, led the league in assists. Just from his impact on the ice, I don’t know that anybody can really compare to him (profile of Fielder can be found here).”

Fielder was part of three WHL championship teams. He led his team in scoring in 13 of 15seasons, led the league in scoring nine times and in assists 13 times.

“Filion also certainly had his moments,” he said. “He was one of two players to lead a Fielder team in scoring (1960-61).”

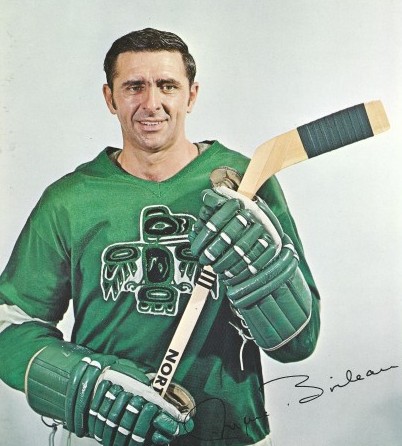

No one served in more varied roles with the Totems than MacFarland, one of more intriguing figures in Seattle sports history. For one thing, he was admitted to the Washington State bar in 1964 while still an active player.

“MacFarland kind of did everything,” he said. “He came to Seattle as a player and worked as a player rep in union negotiations. He won a championship as a player and then won back-to-back championships as a head coach. He was a general manager and part owner of the team. His fingers are all over the franchise from 1957 up until 1970. He was a very big factor during the Totems’ greatest period, and when he left was when things started to fall apart.”

Fielder’s departure didn’t help, either, although his absence had less to do with it than several other factors that affected all WHL clubs. As explained in the book, the NHL muscled its way into the Los Angeles and San Francisco/Oakland markets in 1967-68, depriving the WHL of its two largest cities.

“Things certainly fell apart on the ice for the Totems,” he said. “But part of that was tied to the NHL expansions that made it harder for minor league teams to get players.”

As the Totems swooned on the ice, attendance suffered. They also had a disadvantageous business relationship with the Vancouver Canucks, who owned a stake in the Totems. That didn’t help the consistency of the Seattle roster. The nadir came in 1971-72, when the Totems won 12 games.

“In the pre-Coliseum days (pre-1964) when they were in the Mercer Arena, sellouts were pretty common,” he said. “You were right on top of the ice, and it could get really loud. The small rink lent itself to a very physical style of play, which was why the WHL was a super physical league.

“After they moved into the Coliseum, attendance was kind of hit and miss. You had an arena that held 12,700. Sometimes they’d sell out, and there were times they were getting 5,000-7,000 per game. By the end, maybe there were 1,500 people, and it was like a ghost town.”

Bad as were the early part of the 1970s, the Totems produced one of the great moments in Seattle sports history before their demise became official. Due to the efforts of MacFarland, who worked out the details, the Totems engaged the powerful Russian national team in the Seattle Coliseum Dec. 25, 1971. They predictably suffered a 9-4 loss.

On Jan. 5, 1974, virtually the same Russian team returned to the Coliseum for a rematch.

“The Russians didn’t even suit up their top line to start the game,” Obermeyer said. “When they realized they were in an actual game, they had their top guys suit up for the second period. It wasn’t enough and the Totems won, which was a pretty big deal.

“The final was 8-4 and was considered a pretty big embarrassment for the Russians, losing to a minor league team with a sub-.500 record. For the people who were there, that was a really big sports memory.”

The end of the Totems gets considerable attention, including what he describes as “the NHL debacle.” After owner Vince Abbey was awarded a franchise June 12, 1974, he apparently failed to meet the financial conditions of the expansion agreement and lost the team. The precise hows and whys have yet to be fully disclosed, but popular belief if that Abbey couldn’t come up with the money.

“If the NHL had a problem with Vince as an owner, why would it have awarded him a franchise in the first place? He did get awarded a franchise, and that’s very clear,” he said. “It was there. All Abbey had to do was meet the conditions, and the NHL’s contention was that the conditions did not happen. That’s the conventional wisdom, that the money wasn’t there.

“But there are a lot stories about how it all went down. But at some point the NHL decided it didn’t want to be in Seattle, or it didn’t want to be involved with Abbey, one of the two. I’m not 100 percent sure what happened.

“Over time, memories get muddled and people believe what they want to believe. I talked to (Bill) MacFarland and Abbey about it. I tried to reach out to the law firms (Abbey laid an anti-trust suit on the NHL that dragged through the courts until the late 1980s), but couldn’t get a hold of any documentation. There are definitely still a lot of questions out there.”

While Seattle Totems is a visual feast, it is also packed with information that you would have no hope of knowing if Jeff hadn’t brought it back to life. Consider these random nuggets:

- The Seattle Metropolitans (1915-24), the first American team to win the Stanley Cup (1917), took their name from the Metropolitan Building Co., a property management firm that administered the development of downtown Seattle after the University of Washington moved from “Denny’s Knoll” to its present site (Metropolitan oversaw the construction of the White, Henry, Stuart, Cobb, Douglas, Stimson and Skinner buildings as well as the Metropolitan Theatre and Olympic Hotel).

- The 1917 Stanley Cup final in Seattle featured seven future members of the Hockey Hall of Fame, including three Metropolitans: Frank Foyston, Harry “Happy” Holmes and Jack Walker. The Canadiens countered with four: George Vezina, Newsy Lalonde, Didier Pitre and Jack Laviolette.

- The Seahawks are Seattle’s NFL team today, but were the city’s professional hockey team from 1933-40, playing in the North West Hockey League. They won a league title in 1936 under head coach Frank Foyston, a former member of the Metropolitans, and featured John Houbregs, father of University of Washington basketball All-America choice Bob Houbregs.

- Leo Lassen, the popular radio voice of the Seattle Rainiers Pacific Coast League baseball team for many years, served as a director of the original Totems.

- The original owners of the Totems selected “Jets” as the new team’s nickname. But Seattle Times reporter Hy Zimmerman suggested “Totems” to honor the region’s Native American heritage, and it stuck.

- At its peak in the mid-1960s, the Seattle Totems Booster club included approximately 400 members.

At its peak, the Seattle Totems Booster Club included approximately 400 members. / David Eskenazi Collection

- Harold Snepsts, who played 19 games for Seattle in 1974-75 when they were in the Central Hockey League, was the last Totem to appear in an NHL game. Snepsts retired after playing for the 1990-91 St. Louis Blues.

- Roughly 210 skaters and 25 goaltenders suited up for the Totems between 1958-75.

- When goaltender Al Millar was pulled in the middle of the second period of a game against Calgary during the 1962-63 season, he was replaced by local junior leaguer Lorne Thornycroft, who was literally plucked out of the stands and sent on to the ice.

“The most interesting part was learning more about the players,” Obermeyer said. “These guys were professional minor leaguers. They might have had a cup of coffee in the NHL. They were guys who played minor league hockey for a living at a time when a hockey player didn’t make a ton of money. They were making what a professional working man made. All of these guys worked in the offseason, they had to. They were farmers and carpenters and bartenders. One was a grave digger. They were just regular guys who enjoyed playing hockey.

“Rudy (Filion) and his wife managed a restaurant at a golf course. There was a certain working-class vibe to it. Those guys who played in the WHL, they are still approachable today. They loved to play hockey, nobody was going to get rich. You can sit down and have coffee with these guys and they’ve all got stories.”

Jeff knows many, which is why his website and books carry so much authority. Seattle Totems is another splendid example that adds much to Seattle’s colorful hockey past.

————————————-

Jeff has two signingsm, the first Saturday from 1-3 p.m. at Costco in Shoreline. The second is Tuesday, Sept. 22 from 7-9 p.m. at Third Place Books in Lake Forest Park.

————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

2 Comments

I’ll have to keep an eye out for this book. I grew up watching the Totems in the Coliseum. Used to be like playing with fire sitting behind the goal back then.

Google Global Career Club Make $99 Just In One Hour……….Afterg an average of 19952 Dollars monthly,I’m finally getting 99 Dollars an hour,just working 4-5 hours daily online.….. Weekly paycheck… Bonus opportunities…Payscale of $6k to $9k /a month… Just few hours of your free time, any kind of computer, elementary understanding of web and stable connection is what is required…….HERE I STARTED…look over here

~~~~re..

➤➤➤➤ http://GoogleSpecialFindMillionJobsNetworksOnnetCenter/$98hourlywork…. ⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛⚛