For us Puget Sound-area lifers, it’s sometimes surprising to hear that newer arrivals wonder about the reverence in which Ken Griffey Jr. is held around here. His baseball feats speak well for themselves, but when adults begin to mist up 30 seconds into their storytellings, it may provoke newbie listeners to take a half-step back.

You hadda be here. Almost a generation has passed since his pinnacle deeds of the mid-1990s. With the marketplace seeming to add 10,000 newcomers a day, Griffey’s decade in Seattle drifts incrementally yet inevitably toward the shelf and away from the civic heart.

His induction to the Hall of Fame Sunday in Cooperstown, NY., is a compelling reason to recall that the baseball world for much of the 20th century was convinced that Seattle was a bad baseball town. The fact it was actually a town of bad baseball didn’t occur to anyone who didn’t have to watch it daily.

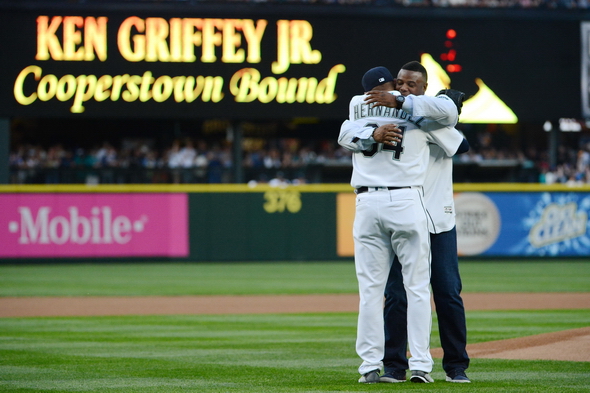

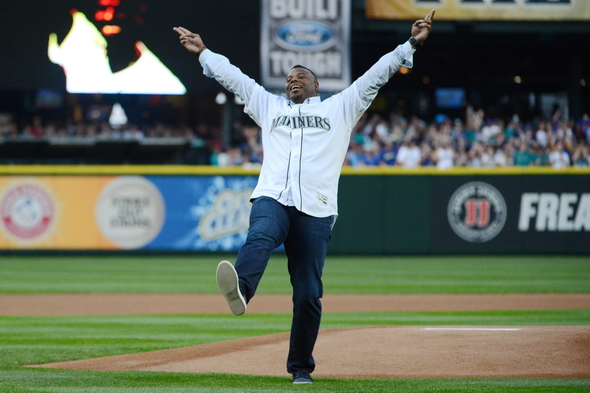

Griffey changed all of that, not only by his deeds but by his exuberance for the game. Then there was that moment in 1990 when Griffeys Senior and Junior took the Kingdome field together. Any witness who was a father or a son still can’t get that out of his throat.

Never has Seattle sports experienced a more transcendent athlete, because he was the prime reason a crippled franchise on the edge of relocation is now anchored in the cultural firmament, 15 playoff-free seasons notwithstanding.

Between the lines, Griffey was the paradigm of ballplaying perfection. Outside the lines, he had a complex web of insecurities that dismayed some and irked others because, as with most of us, he had a hard time explaining himself.

Griffey was the community’s child, in all his glories and aggravations. Arriving as a teenager and departing as a married man with children, he reveled in and recoiled at also carrying a franchise.

When he made the decision to leave in 1999, taking his family closer to his new Florida home as well as his divorcing parents — and to find a ballpark more hitter friendly than new Safeco Field, which he was partially responsible for creating — the development was the most wrenching in my experience in Seattle sports, at least until the Sonics left.

For my 2002 book Out of Left Field, which chronicled the Mariners’ rise from the baseball ditch to the freeway, I had access to those who were involved in the decision by Griffey to exercise the collective bargaining agreement’s “ten-and-five rights” (10 years in baseball, five with the current team) to demand and get a trade to a team on the list of his choice.

In early November 1999, Griffey told his agent, Brian Goldberg, who informed CEO Howard Lincoln and president Chuck Armstrong of the decision. The Mariners’ execs wanted to hear it directly. Along with GM Pat Gillick, they flew to Florida.

Below is an excerpt from the book that describes the episode.

——————————————————–

The club execs planned to talk with Griffey and Goldberg at an Orlando hotel meeting room. “Kenny didn’t want to come,” Goldberg said. “He said, ‘We’re friends, and a meeting makes things too formal.’ I think they knew what his decision was, but since things came out bad with Randy Johnson, they didn’t want a repeat.”

Griffey finally relented. He met Gillick for the first time, and the five men chatted briefly before Griffey explained the personal and family concerns that had become paramount.

Then came the crossroads moment: He said he no longer wanted to be a Mariner.

Gillick asked: “What if we go to the World Series?”

“No,” Griffey said. “It’s about my family.”

Armstrong, who was club president under former owner George Argyros in 1987, when the Mariners chose Griffey with the No. 1 pick in the amateur draft, asked to speak to Griffey privately. The two and Goldberg left the room and walked down the hall to the lobby for a few minutes. After 13 years of spectacle, injury, sadness and breathtaking joy, The Kid who became The Man in Seattle sports and the most popular baseball player on the planet, started to cry. So did Goldberg. So did Armstrong.

“We gave each other a hug, and I told Junior he’d be OK,” said Armstrong. “He’s a friend. I miss him.”

Griffey left the hotel. Goldberg and Armstrong composed themselves, returned to the meeting, and said Griffey was solid in his decision, so let’s move on.

After a discussion of some wording in a joint statement, the meeting quickly broke up. A call was made to the offices in Seattle. Bart Waldman, the attorney who worked on the contracts with Griffey, will never forget the despair in the office that afternoon.

“We were thunderstruck,” said Waldman. “This came out of the blue . . . he didn’t want to stay. It was a very tough day.”

Said assistant GM Lee Pelekoudas: “You didn’t take him for granted, but he’d been a part of the organization for so long, What we accomplished with and because of him . . . all of a sudden, you say, ‘Oh, shit.'”

———————————————————-

After more than three months of tense, awkward and often public negotiations between the Mariners and the several clubs on his list, Griffey was traded to his hometown of Cincinnati Feb. 10, 2000. The Mariners obtained CF Mike Cameron and three guys who never amounted to much for one of the greatest players in history.

Griffey took quite a bit less money from the Reds than the Mariners’ final offer ($138 million million over eight years), and he took on even more pressure as the prodigal son returned.

Said Cincinnati radio personality Bill Cunningham: “For a thousand years, Cincinnati will shine as the brightest star. Griffey has lit a thermonuclear fuse, fallout from which will cover the town forever and ever.”

Or not.

For reasons largely due to declining health, it didn’t work out too well for Griffey in Cincinnati.

But that isn’t what Sunday is about. It’s about Griffey’s first 11 uproarious years in Seattle, where he brought the sport from the margins to center stage.

The time when he was The Kid. As were we all who bore witness.

4 Comments

I remember Reds GM Jim Bowden, new to the GM game at age 31, being pretty proud of himself for the deal he swung on Pat Gillick. He thought he got Junior for less than market value and didn’t give up a lot for him and then bragged that he stared down Gillick in his demands for 2B Pokey Reese to be included in any deal for Junior. The M’s, as all diehard M’s fans know, got Cammy, Brett Tomko and two prospects in Antonio Perez and Jake Meyer. Really, just getting Cammy alone was more than enough considering the contributions he did during his Mariners career.

That being said, I’m looking forward to Junior’s day. When Randy was inducted I was thoroughly impressed with his speech. Despite the fact that he was going in wearing a Diamondbacks cap and had six teams on his resume his tenure with the M’s dominated. Junior will do no less. It’ll be like firing up the Delorean and going back to 1979 again. Actually probably 1969.

Finally, I hope, my Griffey $wag will go up in value. The trade was a heart breaker.

“All is well that ends well.” One of the greatest to be inducted going in wearing an M’s cap. “My oh my.” “Thanks for the memories,” Jr.

Ode to Baseball

The Kid. Junior. Goofy Smile. Sweetest swing you have ever seen. Tomorrow an all-time great – the greatest player I’ve watched in person play – Ken Griffey Jr will take his rightful place among the best of the best. I’ll be watching with an old friend as a childhood hero tips his cap to the crowd one more time. And I’ll be in Seattle August 6th to watch his induction ceremony in Seattle with new friends. There are so many favorite memories of Griffey – the backwards hat, father and son back to back homers (wow!), the iconic smile at the bottom of the pile after Edgar’s double heard ‘round the world, the amazing catches… https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4FS8UxXiaPw . Junior was also such a class act and if you haven’t watched his speech when he was inducted into the Mariners Hall of Fame you have to watch this https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8hLTka0S3MA.

Baseball for me somehow transcends just another sport. The sound of the bat on the ball. The snap of the ball hitting the mitt for a strike. The contrast of the grass and dirt. The straight chalk lines. The long tradition. The precision of the rules. No time limit – no matter how far you are down you can come back up to the last out. The failure – if you fail 70% of the time – that’s success. I love that everything is tracked. I love that there is a team but it is also mano a mano. One batter vs one pitcher in the ninth for the win. No other sport is quite like baseball.

My favorite baseball movie is The Natural. Robert Redford’s character Roy Hobbes is supposed to be the best pitcher ever but he gets derailed by a gunshot and life careens off course. He comes back 20 years later as a 40 year old rookie batter – fights through a grueling season – is injured but hits one last, glorious home run. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gjk3RsytFZg Baseball is beautiful. My second favorite baseball movie is “A League of Their Own” where Dottie Hensen is the better player but in the last game her kid sister, Kitt, just wants it more. You taste the pain of defeat in Tom Hanks’ Jimmy Duggan. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a46FsHMRPkc Duggan has the perfect line, “the hard is what makes it great.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ndL7y0MIRE4 There is a romance to baseball – the sense that the impossible can happen – the perfect game – the homer at the perfect moment. I was at the game where the most incredible homer in Mariner’s history was hit. Bottom of the ninth, bases-loaded, down by 3, two-outs – and Phil Bradley crushes a grand-slam. I was there. I saw it happen with my Dad. It is quantifiably the rarest of homers in Mariners History. https://www.sportspressnw.com/…/martins-walk-off-a-rare-one-in-m… . It is this potential for anything to happen – no matter how ugly it has been before – right now – this at bat – it can all change – it is what makes baseball great. “How can you not be romantic about baseball.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xn7C6jgl0RI

And to one who had more than his fair share of making it great –

Cheers Junior